Preservation Society of Charleston gets support for documenting Black cemeteries

Firefighter Derek Norton (from left), volunteer Jacob Lutz, firefighter Nick Boyer and firefighter Rob Tackett helped with some excavation work at the Heriot Street Black cemetery last month. The firemen are based across the street at Engine Company 9. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Firefighter Derek Norton (from left), volunteer Jacob Lutz, firefighter Nick Boyer and firefighter Rob Tackett helped with some excavation work at the Heriot Street Black cemetery last month. The firemen are based across the street at Engine Company 9. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Now, the Preservation Society of Charleston wants to make it easier to discover details about these sacred places before the bulldozers and cranes get to work. A $50,000 grant from the National Park Service will help the nonprofit launch its “Mapping Charleston’s Black Burial Grounds” initiative, a collaborative effort to produce a comprehensive inventory of the city’s lost, forgotten, overlooked and unprotected cemeteries.

The headstone for Samuel Matthews, located in the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

The headstone for Samuel Matthews, located in the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Red flags mark graves behind 88 Smith St. in September 2020. The property was once Trinity cemetery, where 1,653 Black people were buried. File/Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Red flags mark graves behind 88 Smith St. in September 2020. The property was once Trinity cemetery, where 1,653 Black people were buried. File/Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

‘What the community wants’

The efforts to identify and secure graveyards in the city began in earnest after remains were found in 2013 near the Gaillard Center when the building was being renovated. The late Ade Ofunniyin, an anthropologist and adjunct professor at the College of Charleston, started the nonprofit Gullah Society and assembled a small team of researchers who began the process of documenting Black burial grounds in the area. The Gullah Society dissolved after Ofunniyin’s death in 2020, but its work continues. The Anson Street African Burial Ground Project has been investigating the remains of 36 people found near the Gaillard and arranging for a permanent memorial. Leaders at the Preservation Society have embraced Ofunniyin’s mission and made it their own. The International African American Museum has thrown support behind the latest initiative and the city has endorsed it. “Together we recognize the urgent need for more data and information about African American burial sites to help inform land-use planning so as to avoid harmful impacts to gravesites, especially those which are unmarked,” Mayor John Tecklenburg wrote in a letter of support that accompanied the grant application. A large lot on Heriot Street, between the Charleston Squash Club and Carter’s City Self-Storage, is an old Black cemetery where more than 2,000 people were buried. Grant Mishoe/Provided

A large lot on Heriot Street, between the Charleston Squash Club and Carter’s City Self-Storage, is an old Black cemetery where more than 2,000 people were buried. Grant Mishoe/Provided

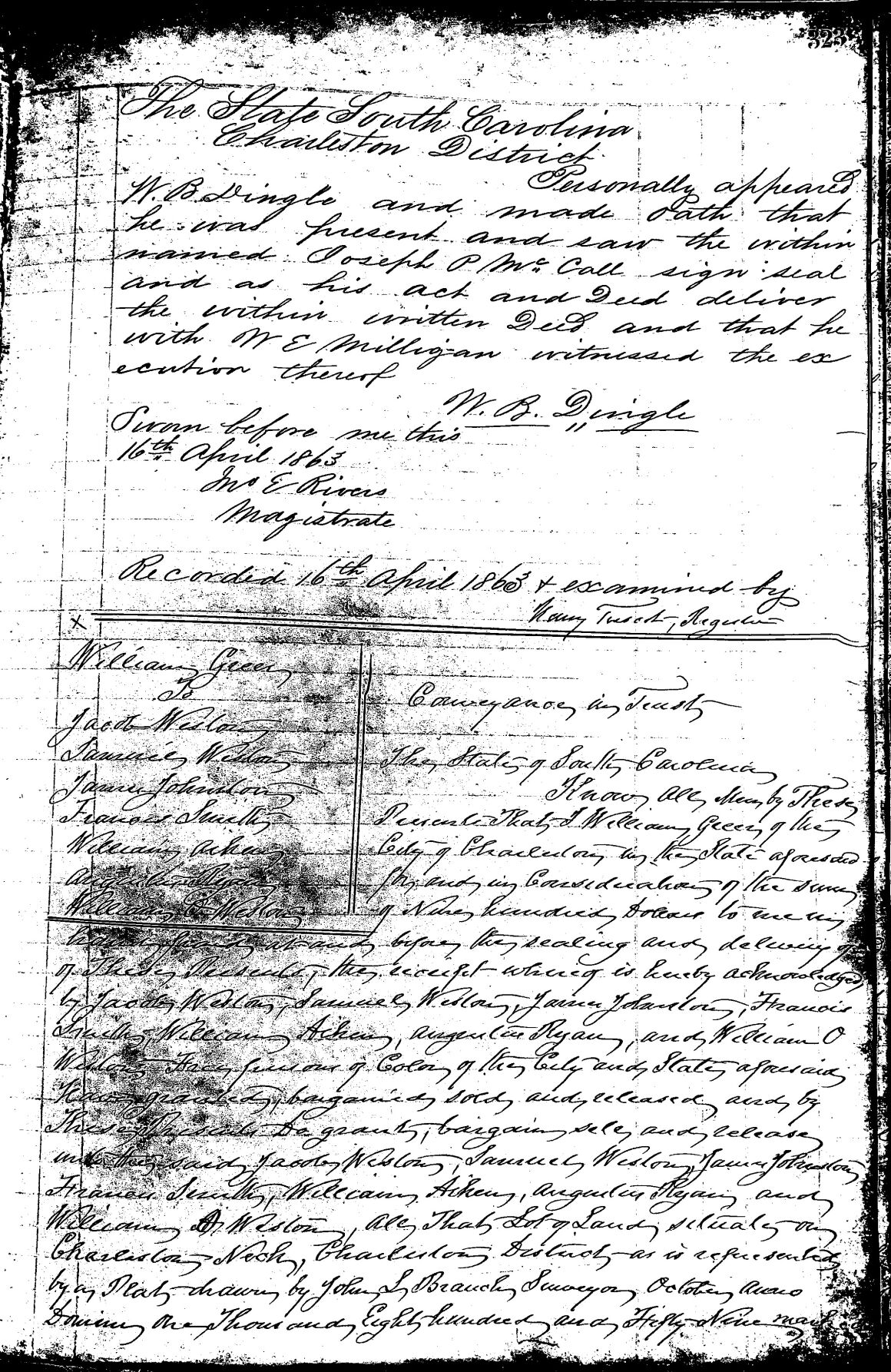

The first page of a three-page property deed for the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

The first page of a three-page property deed for the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

More proactive

Robert Summerfield, the city’s director of planning, said incorporating information provided by the Preservation Society into the GIS system will enable developers (and anyone else) to access a new layer of data regarding burial sites during the preparation phase of a construction project. He believes this will result in fewer surprises. “It’s 100 percent about trying to be more proactive, so people don’t get caught up after investing millions in a project that could require changes,” Summerfield said. He added that the collaboration with the Preservation Society is welcomed. “You’ve got to have somebody who can look at the older records, maps and survey data that may be available, then piece it together, like a true Indiana Jones-type of project,” he said. “Like everything, it’s a resource issue, which is why it’s really great that we have a partner in the project.”The grant money likely will be spent researching the Heriot Street cemetery, Turner said. The archaeological firm Brockington and Associates will be engaged to help define the boundaries, conduct surface testing and perform other survey work.

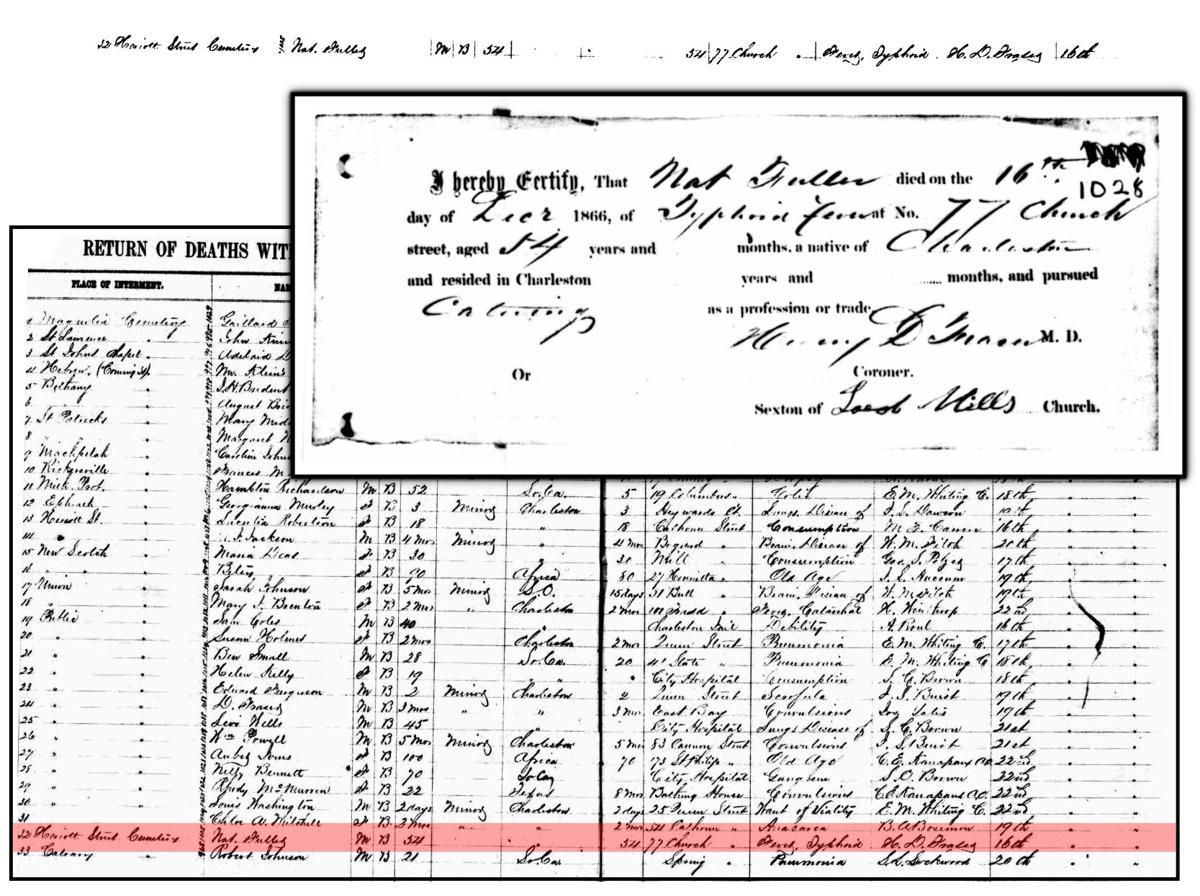

African American chef Nat Fuller is among the people who were interred at the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Researcher Grant Mishoe, who previously was affiliated with the Gullah Society, has been investigating this property for years.

Among the more than 2,000 people buried there are chef Nat Fuller, two victims of the 1886 earthquake and at least four Black firefighters. Mishoe estimates that about 80 people were laid to rest in the cemetery each year beginning in 1875.

For years, it was thought the property had no deed. The city used it to store heavy equipment for a while, and occasionally sent someone to cut the grass. Mishoe found the deed, which dates to 1863. The land once was part of Rat Trap Plantation and it was purchased by a group of African Americans after the owner died and his property was subdivided into smaller lots.

African American chef Nat Fuller is among the people who were interred at the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Researcher Grant Mishoe, who previously was affiliated with the Gullah Society, has been investigating this property for years.

Among the more than 2,000 people buried there are chef Nat Fuller, two victims of the 1886 earthquake and at least four Black firefighters. Mishoe estimates that about 80 people were laid to rest in the cemetery each year beginning in 1875.

For years, it was thought the property had no deed. The city used it to store heavy equipment for a while, and occasionally sent someone to cut the grass. Mishoe found the deed, which dates to 1863. The land once was part of Rat Trap Plantation and it was purchased by a group of African Americans after the owner died and his property was subdivided into smaller lots.

Work to do

Last month, Mishoe and his colleagues spent some time examining the cemetery. They found about 35 headstones, metal nameplates, casket handles and other small pieces of hardware before deciding to stop. Assisting them for a spell were a few firefighters from Charleston Fire Station 9 across the street. They had heard about the Black firemen interred there and wanted to help.

Amos Baxter died in 1883 and was buried in the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

Amos Baxter died in 1883 and was buried in the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided