Turner: How Charleston treats its ancestors reflects who we are

This opinion piece was originally published by The Post and Courier, Oct. 8, 2025.

Graveyards are a subject of everyday conversation these days. And no, not just because we are getting in the Halloween spirit. It’s because, in Charleston’s haste to meet the demands of the modern age, these sacred places are increasingly seen as sacrificial.

Basic dignity for the lives of those interred before us is at stake. As real estate pressures rise, advocates are racing to humanize Charleston’s burial landscape, lest “rest in peace” become more of a question than a promise.

The College of Charleston’s proposed dorm at 106 Coming St. is a startling recent example. The land was zoned for dense development two years ago with no review of what or who was beneath the pavement. Without local archaeological protections, this practice has become par for the course. The previous owner was able to fetch a sale price to match the site’s new potential and sold it to the college in January.

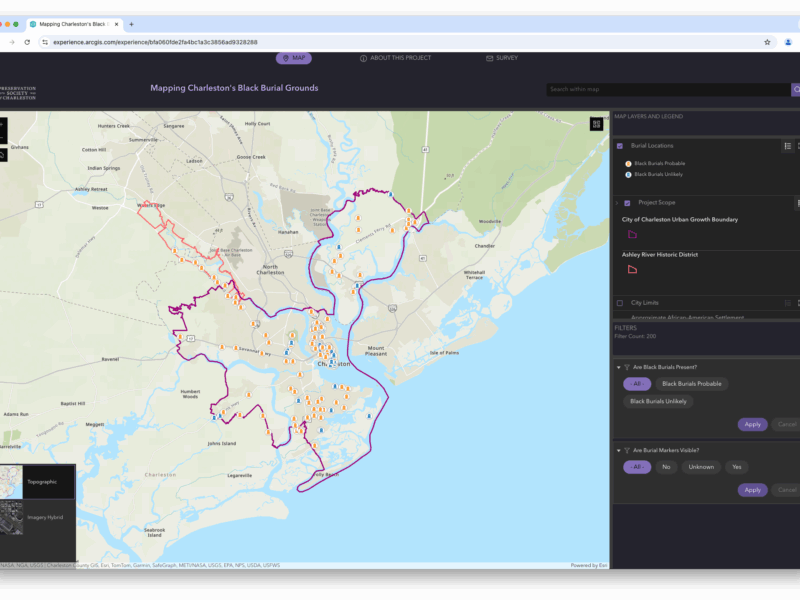

Far from a blank slate, research shows that this piece of land contains the most intact portion of an 18th-century burial ground segregated for thousands of people of African descent. Records are clear that the city operated the site, in part, to prevent the disposal of bodies into Charleston Harbor when ship traffic from the transatlantic slave trade reached its peak in America.

The College of Charleston deserves credit for hiring a qualified historian to confirm these hard truths, engaging the community and, most recently, backing off its aggressive timeline. But it has taken — and will continue to require — a dogged educational and advocacy effort to ensure harm is avoided at all costs. Charleston’s “Protect and Respect the Bodies” coalition has been instrumental. It is just one voice in a national movement underway bringing attention to the threats to burial places and honoring the lives of our ancestors.

Burial ground advocacy is nothing new; basic protections are as old as time. But history is also replete with examples of disparity, and not all have been afforded access to the legal tools to prevent harm. As author Kevin Sack details in his recent book, “Mother Emanuel,” an impetus for the founding of the first AME church in Charleston came in 1817, when the white trustees of Bethel Methodist Episcopal, then integrated, chose to build atop the segregated black portion of its burial ground.

This story is instructive for the historic preservation movement, which is often solely associated with architecture. Our objective is not only to maintain a beautiful aesthetic environment crafted with care through time, but to preserve places of cultural meaning that are fundamental to our community’s identity. Specifically, the actions of early AME church congregants point to cemeteries as important not only for religious rituals, but for equal rights.

British Prime Minister William Gladstone famously compared the manner a nation’s citizens care for their dead with the “tender mercies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land and their loyalty to high ideals.” As Charleston plans for its future, we must contend with a legacy of haphazard, inconsistent and unjust treatment of its burial grounds. But there is always a time to turn the page.

We hope you will join the community dialogue to determine what the ethical care and treatment of our buried requires in this time. It is a chance to cut past the noise and rebuild our common bonds as stewards of our shared heritage.

Brian Turner is the president and CEO of the Preservation Society of Charleston.