Located on the Edisto River, Jehossee Island is an uninhabited former rice plantation where hundreds of years of undisturbed Lowcountry history form a fascinating cultural landscape. Once one of the most productive rice plantations in the American south with one of the largest enslaved populations, Jehossee has the potential to contribute significantly to the modern understanding of pre-Civil War rice cultivation in the Lowcountry.

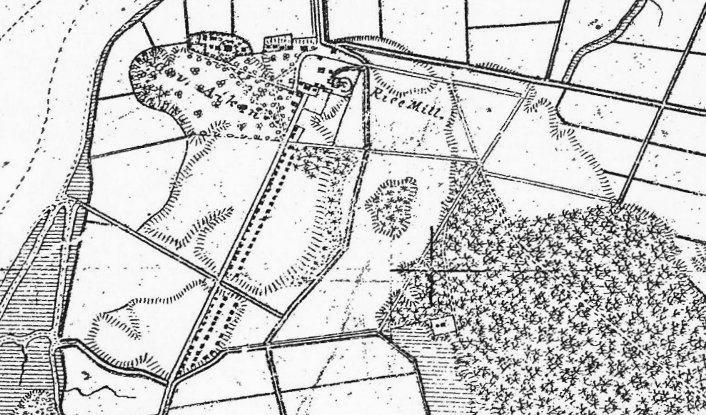

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Jehossee Plantation’s 4,000+ acres were owned by some of the Lowcountry’s most prominent planter families. For nearly half a century between 1776 and 1824, Jehossee was owned by the Drayton family, passing to Governor William Aiken Jr. in 1830. Rice cultivation at Jehossee relied on complex infrastructure, including major canals, fields, berms, dikes, rice trunks, and an impressive brick chimney used for threshing harvested rice. A substantial ruin of the chimney still stands on site today and is one of the few remaining examples in the Lowcountry.

Rice production at Jehossee relied on the labor of an estimated 700-1,200 enslaved people at its peak between the 1830s and 1860s. Written accounts and a site plan completed as part of the 1856-1857 U.S. Coast Survey indicate the presence of an extensive village built by and for Jehossee’s enslaved population, including a recorded 84 wood-frame houses, a church, a hospital, a store, and an overseer’s house among other structures. Today, the 1830s overseer’s house stands largely intact while sites of former buildings are marked only by remnants of brick foundations and chimneys. Like the rice chimney, the overseer’s house is significant as one of the few remaining examples of this building type in North America.

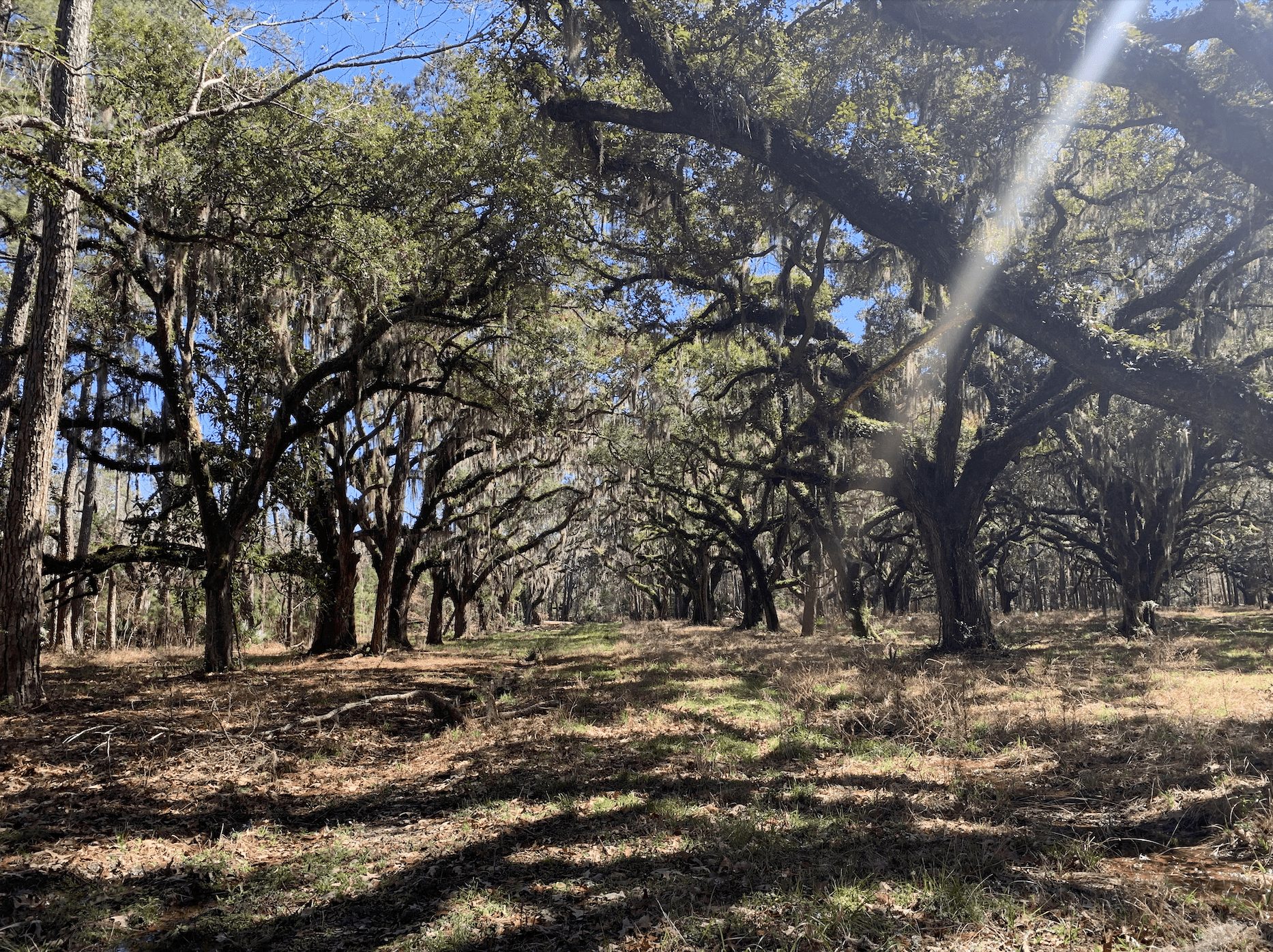

In the roughly 150 years since rice cultivation ceased at Jehossee, the vast landscape remains remarkably unaltered. The level of general preservation on the island can be largely attributed to the creation of the Intracoastal Waterway in 1920 that destroyed the Jehossee causeway, the island’s only convenient link to Edisto, as well as the mainland. As the island grew in isolation, use of the property waned with low-impact recreation like waterfowl hunting being the primary draw to the property by the mid-twentieth century. Consistent ownership of the property also played a significant role: Governor Aiken’s descendants remained in possession of Jehossee until 1993 when the land was deeded to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service which remains the steward of the site today.

In recent years, vegetative growth has obscured many of the site’s physical features, and successive hurricanes damaged the overseer’s house and the rice chimney. However, defining characteristics of the historic landscape remain with great potential for the study of resources both above and below ground. The undisturbed nature of Jehossee represents a rare opportunity to examine the evolution of a Lowcountry rice plantation and the landscape of slavery from the 18th through the early 20th century.

The PSC continues to work closely with our partners to document Jehossee Island and secure funding for the stabilization and preservation of at-risk structures on site. Join us in ensuring more sustainable, long-term protection and interpretation of this significant historic property by donating here.