More proactive

Robert Summerfield, the city’s director of planning, said incorporating information provided by the Preservation Society into the GIS system will enable developers (and anyone else) to access a new layer of data regarding burial sites during the preparation phase of a construction project. He believes this will result in fewer surprises.

“It’s 100 percent about trying to be more proactive, so people don’t get caught up after investing millions in a project that could require changes,” Summerfield said.

He added that the collaboration with the Preservation Society is welcomed.

“You’ve got to have somebody who can look at the older records, maps and survey data that may be available, then piece it together, like a true Indiana Jones-type of project,” he said. “Like everything, it’s a resource issue, which is why it’s really great that we have a partner in the project.”

The grant money likely will be spent researching the Heriot Street cemetery, Turner said. The archaeological firm Brockington and Associates will be engaged to help define the boundaries, conduct surface testing and perform other survey work.

Researcher Grant Mishoe, who previously was affiliated with the Gullah Society, has been investigating this property for years.

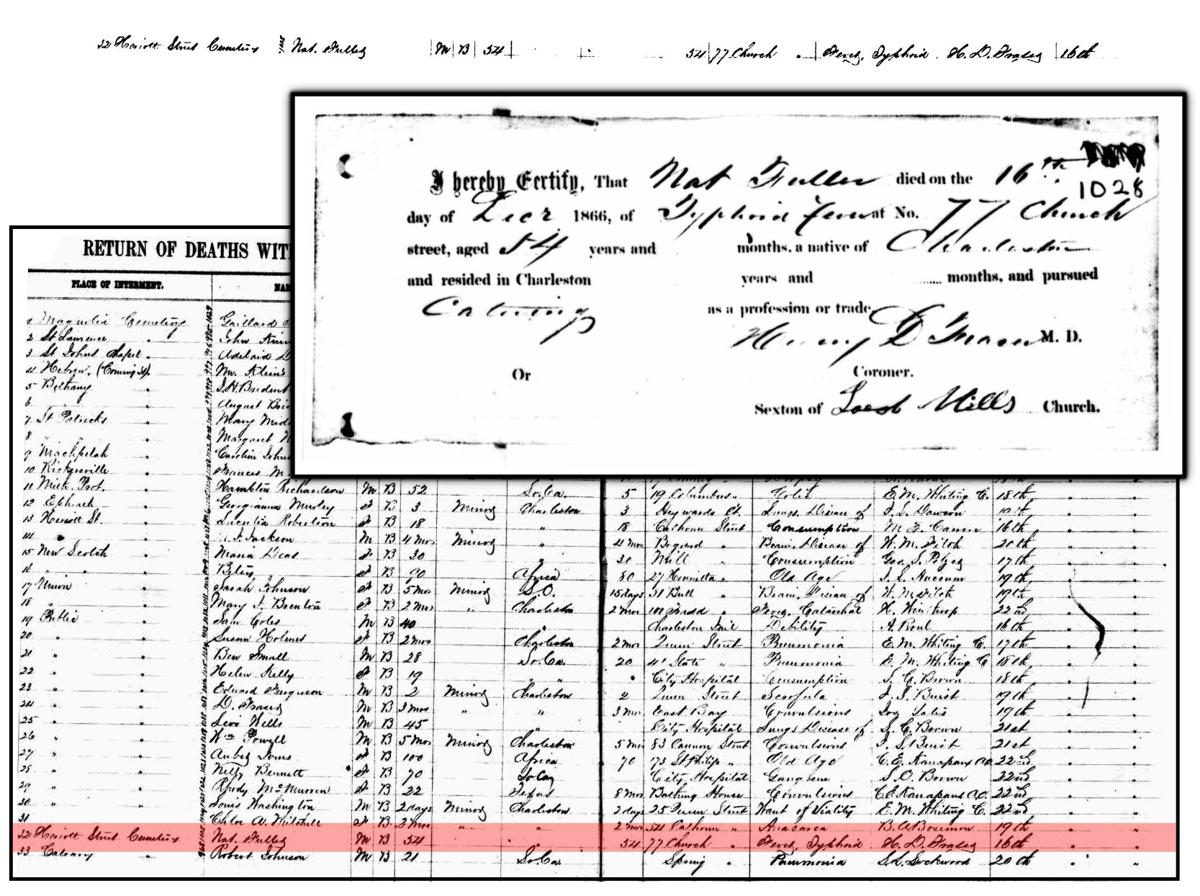

Among the more than 2,000 people buried there are chef Nat Fuller, two victims of the 1886 earthquake and at least four Black firefighters. Mishoe estimates that about 80 people were laid to rest in the cemetery each year beginning in 1875.

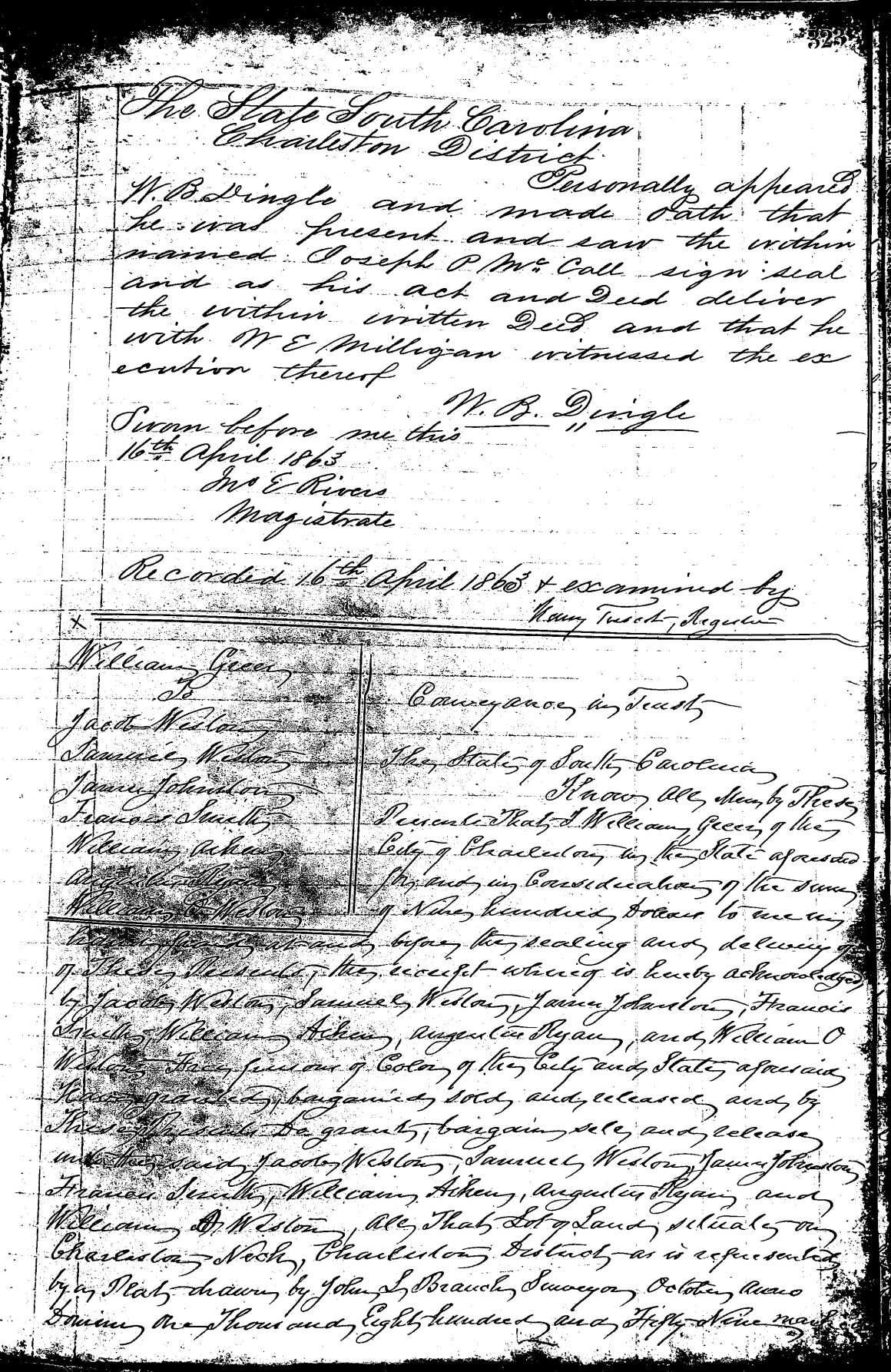

For years, it was thought the property had no deed. The city used it to store heavy equipment for a while, and occasionally sent someone to cut the grass. Mishoe found the deed, which dates to 1863. The land once was part of Rat Trap Plantation and it was purchased by a group of African Americans after the owner died and his property was subdivided into smaller lots.

Work to do

Last month, Mishoe and his colleagues spent some time examining the cemetery. They found about 35 headstones, metal nameplates, casket handles and other small pieces of hardware before deciding to stop. Assisting them for a spell were a few firefighters from Charleston Fire Station 9 across the street. They had heard about the Black firemen interred there and wanted to help.

Mishoe said the cemetery includes some caskets just 12 inches from the surface, suggesting the possibility of more than one layer of people laid to rest within. Some of the headstones featured ornate decorations, others mere scratchings. One they found was made of granite and included a brass nameplate, indicating that the family could have been of some means.

A few of the people buried in the cemetery were born in Africa and Haiti. Most were born in South Carolina.

“This was the first cemetery I started working on 30 years ago,” Mishoe said. “There was equipment parked on it. People walked through it. It was out of sight, out of mind.”

Not anymore.

The first page of a three-page property deed for the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided

The first page of a three-page property deed for the Heriot Street cemetery. Grant Mishoe/Provided