Media Coverage

Work resumes at 88 Smith St. as preservationists fret about gravesites on the property

preservation-admin , July 9, 2021

Read the original Post and Courier article here

Red flags mark graves behind 88 Smith St. in September 2020. The property was once Trinity cemetery, where 1,653 Black people were buried. File/Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

By Grace Beahm Alford gbeahm@postandcourier.com

The owner of 88 Smith St., a private home in downtown Charleston where the property encompasses all or most of one Black burial ground and a portion of another, resumed renovation work after receiving permits from the city.

A city building inspector halted the work July 6 for lack of proper permits as members of the historic preservation community expressed concerns about the potential for damaging the graveyards.

On April 16, Ram Jack Foundation Repair applied for a permit from the city to “install 16 helical piles for foundation repair,” according to the city’s building inspections division. The permit was issued April 22.

“The city had no option but to grant the permit as it currently has no law on record that requires landowners to protect and preserve burial sites,” noted the Preservation Society of Charleston in a July 9 blog post.

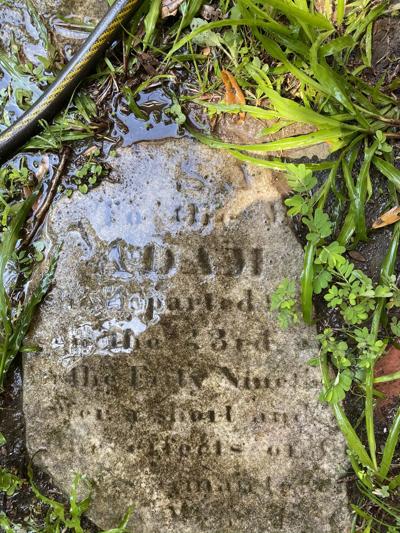

The work required driving piles into the ground, and this likely disturbed existing graves nearby, according to Grant Mishoe, a researcher of burial grounds who had been coordinating with property owner Steve Tsafos to secure some of the gravestones.

Mishoe received help from Grant Gilmore, a professor of historic preservation at the College of Charleston. Both men said some gravestones they had been examining on site and are hoping to relocate to a temporary holding space had been moved from one part of the backyard to a ditch at the rear of the yard.

It is illegal to knowingly remove graves without proper authorization, according to state law. Municipal and county governments have jurisdiction over grave removals. The Department of Health and Environmental Control has jurisdiction over historic cemeteries on public property or when DHEC permitting is required.

Tsafos purchased the property for $600,000 on behalf of his daughter Alyssa Tsafos in March, records show. Since then, he has been making improvements. The newly acquired permits enable him to continue renovation work on the structure only.

Two African American cemeteries, Ephrath and Trinity, are located in the area just south of Calhoun Street. Ephrath contains the remains of nearly 2,000 people and extends from Calhoun Street through what is now the backyard of 88 Smith St. Trinity contains the remains of more than 1,600 people buried beneath and around the house.

Together, these two Black cemeteries contain the remains of more than 3,600 people; about two-thirds can be found on 88 Smith St. property, according to research conducted by The Gullah Society.

Among those buried at Trinity cemetery was Mary Julia Foster, age 33. She died in 1876. File/The Gullah Society/Provided

The Gullah Society/Provided

Eric Poplin, senior archaeologist with Brockington and Associates, said he worked on the site before Tsafos bought the property and determined, thanks to the use of ground-penetrating radar, that the lot was full of anomalies indicating likely graves.

Poplin’s work was part of a due-diligence effort contracted by previous buyers who opted not to go through with the purchase, he said.

“The present owner came to us early this year or late last year,” Poplin said, adding that Tsafos knew that the property was full of graves. “We gave him proposals to complete the (archaeological) work, and recommended that he look elsewhere.”

It is unclear whether Tsafos or his daughter were aware of the requirement under state law to provide certain members of the public access to the site.

Tsafos, who operates a bowling alley in Goose Creek, did not return messages left on July 6 and 9.

According to the S.C. Code of Laws, an owner of private property on which can be found a cemetery or burial ground or grave must allow ingress and egress to family members and descendants of the deceased, an agent representing the family, a plot owner, anyone participating in a burial, or a genealogy researcher with written permission from family members, descendants or the property owner or occupant.

Access must be granted to those visiting graves, maintaining the site, burying the dead, or conducting research. Such access must be requested of the property owner in writing, and the owner (or his representative) has 30 days to respond and provide reasonable arrangements.

Brian Turner, director of advocacy for the Preservation Society, said the city should play a bigger role in protecting such sites.

A provision of state law, Section 6-1-35, grants municipalities and county governments authority “to preserve and protect any cemetery located within its jurisdiction which the county or municipality determines has been abandoned or is not being maintained.” Local governments are further authorized by law to spend public funds, and use inmate labor, to safeguard cemeteries.

But this authority rarely is invoked, Turner said. And property owners can defend against allegations of graveyard damage by claiming that the city chose not to intervene to regulate underground objects, he said.

Among those buried at Trinity cemetery was Mary Julia Foster, age 33. She died in 1876. File/The Gullah Society/Provided

The Gullah Society/Provided

It can be difficult to prove that someone desecrated a grave knowingly and willingly, Turner added. Without an official inventory accessible to the public, property owners can claim they just didn’t know about the graves in their backyard.

“There’s a rationale for the city to do more, and I would hope that events like this would spearhead some of that conversation,” Turner said.

The Preservation Society would be an eager participant, but any solution should be collaborative in nature and involve those with an interest in identifying, documenting, preserving and maintaining the city’s many burial grounds, Turner said.

Charleston could look to other examples, such as the Horry County Cemetery Project, or efforts in Cobb County, Ga., which formed a Cemetery Preservation Commission, and where county officials can bill a property owner for any cleanup and maintenance.

Charleston officials expect to resurrect an archaeological ordinance and present it to City Council for consideration perhaps by late summer, spokesman Jack O’Toole said. The ordinance, if passed, would enable the city to hire a staff archaeologist whose mission could include oversight of burial grounds.

“Protecting historical cemeteries is the next logical, and important, step in our ongoing efforts to preserve Charleston’s history,” O’Toole said in a statement. “The city is currently working with the preservation community and others on both an archeology ordinance and a standalone cemeteries ordinance, each of which should help us make real progress on this issue before the year is out.”

It’s complicated. Some burial grounds are known, others unknown; some are on public land, others on private property; some are maintained, others abandoned. What’s more, the presence of a graveyard can depress property values.

The questions are urgent and significant, Turner said. To what extent is the city willing to regulate private property? How can graveyard protection efforts ensure that privacy and confidentiality are respected? What can be done to protect the interests of property owners, yet hold them accountable for any damage or compromise to the integrity of a historic site? And how can Black people and White people work collaboratively toward common goals?

“It needs to be a community conversation,” he said.

Stay up to date on PSC news by subscribing to our newsletter.