History

Lost History: Rediscovering Union Pier’s Historical Wharves and Their Cultural Impact

preservation-admin , June 2, 2023

Research and writing by Laurel M. Fay

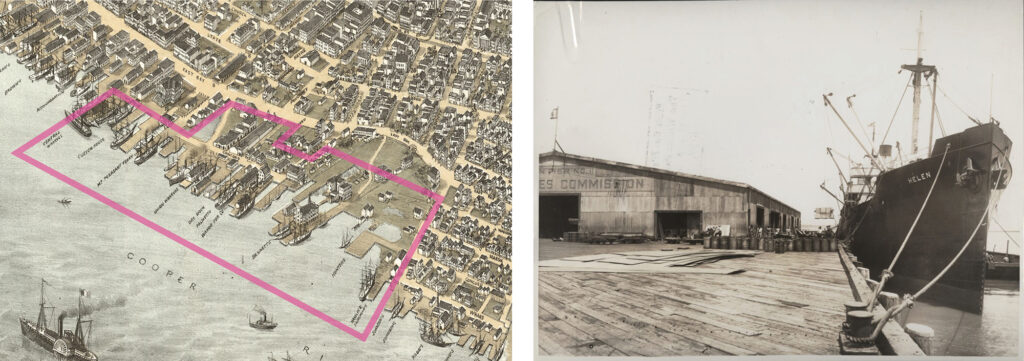

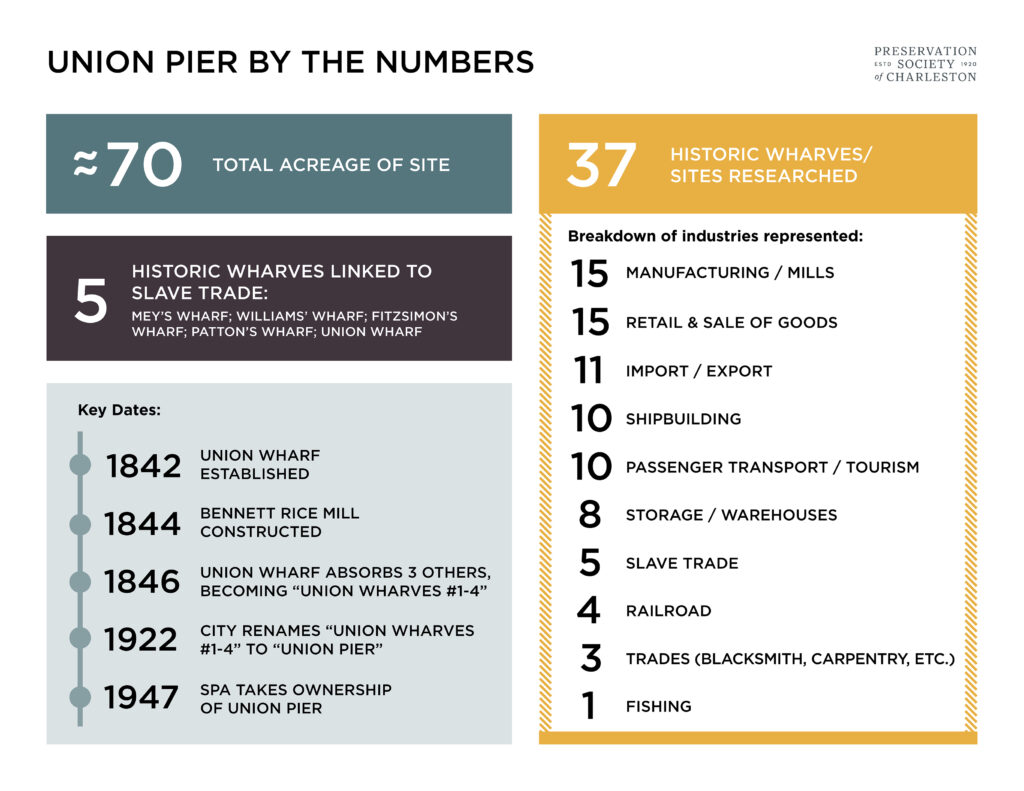

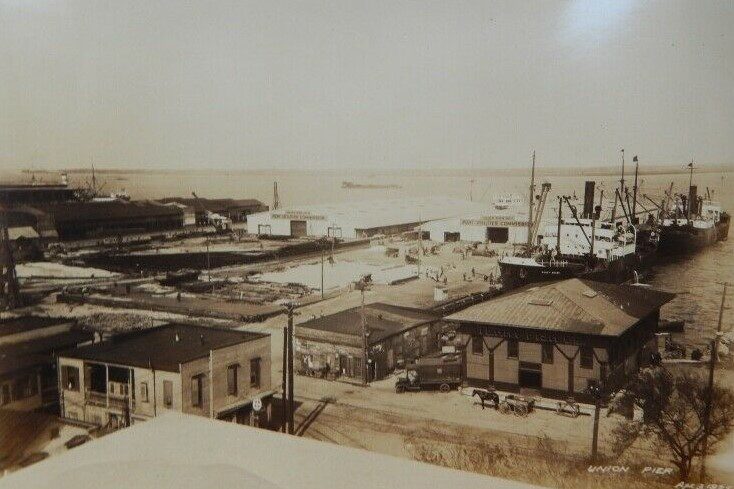

The massive 70-acre concrete slab that comprises present-day Union Pier might, at first glance, seem like a blank slate, but it has a rich, storied past. Historical maps, newspapers, photographs, and other archival resources reveal that the wharves that existed within the Union Pier property footprint served as an anchor for Charleston’s domestic and international trade and manufacturing industries, and had an undeniable impact on Charleston’s cultural and economic development. Union Pier is far more than meets the eye.

A Portal for Domestic and International Trade

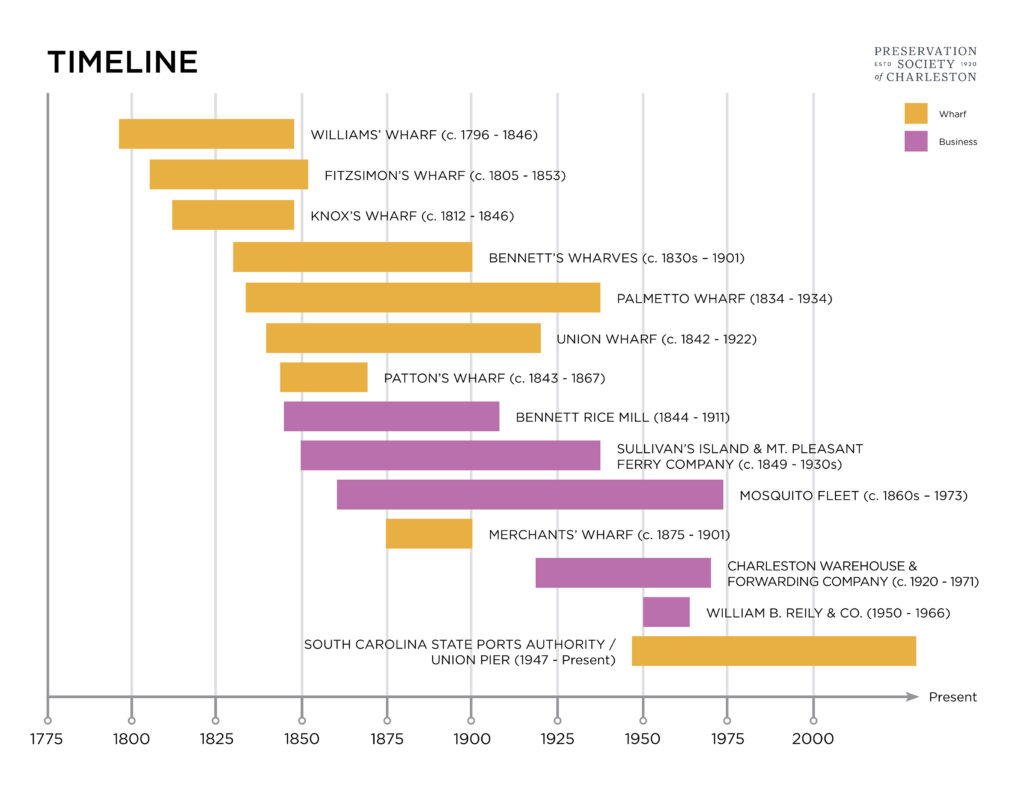

“Union Wharf” was one of the busiest wharves in Charleston when it first appeared in the historical record in 1842. Many wharves occupied the property in the 19th century before Union Wharf expanded and was ultimately consolidated.

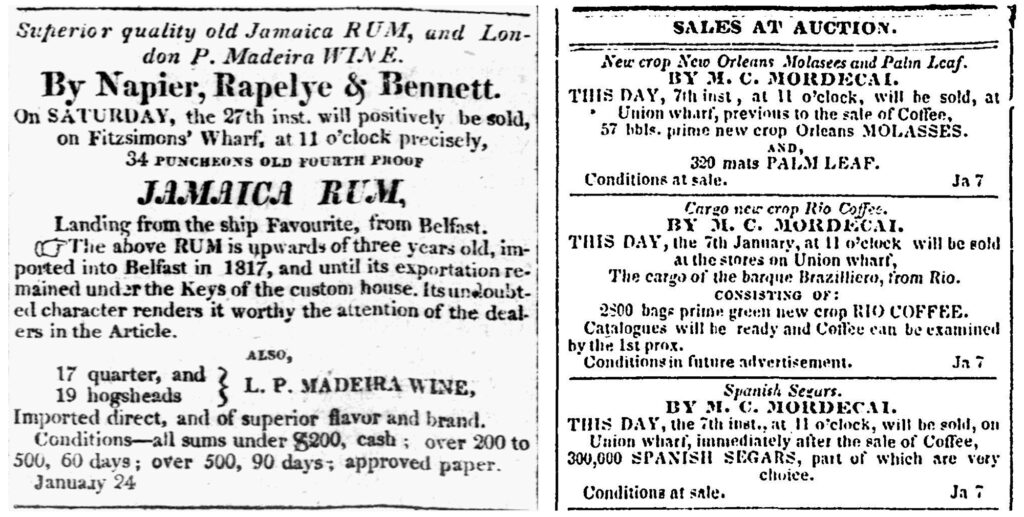

A diverse array of local and imported goods were available for sale, such as fresh seafood, cotton, rice, sugar, salt, coffee, fruits, Spanish cigars, molasses, sugar-cured hams, Irish potatoes, Caribbean spirits, lumber, coal, iron, and much more. Some wharves, like Palmetto and Union wharves, operated stores where people could purchase goods.

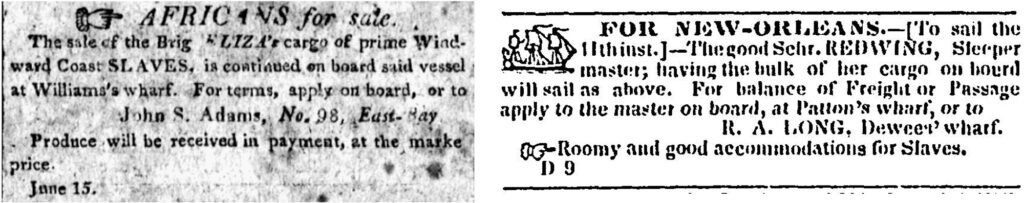

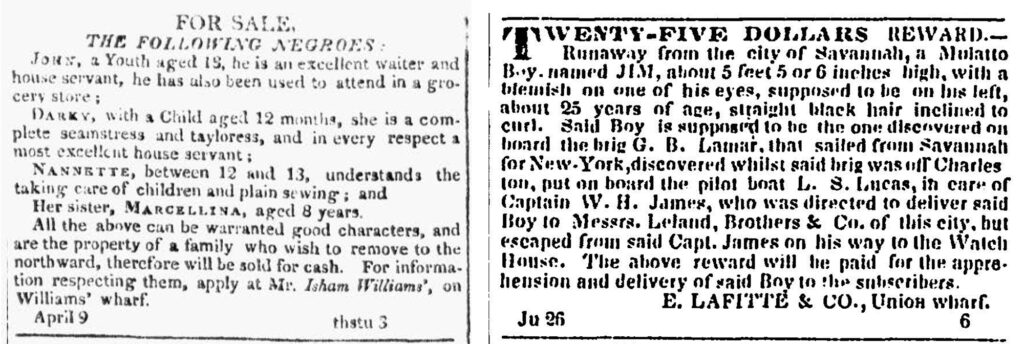

There were five wharves in this area that were associated with the slave trade: Mey’s Wharf, Williams’ Wharf, Fitzsimon’s Wharf, Patton’s Wharf, and Union Wharf. Among these, Williams’ Wharf had the highest number of recorded transactions related to the buying and selling of enslaved Africans. During the first half of the 19th century, newspapers advertised the sale of “prime Windward Coast Slaves,” as well as individuals trained in trades, who were often sold to settle estates or pay debts. Some vessels were advertised as having passage for enslaved people. Other ads publicized rewards for capturing runaway slaves that could be collected on these wharves. Gadsden’s Wharf, just north of Union Pier, is known for being one of the most heavily trafficked import locations for enslaved Africans on American soil, and neighboring docks also contributed to making Charleston a hub for the buying and selling of enslaved African people.

An Early Hub of Industry and Manufacturing

The wharves once located on what is now Union Pier made for a thriving neighborhood of industry and manufacturing that helped establish Charleston as a major 19th century economic player. Blacksmiths, carpenters, ironworkers, manufacturers, shipbuilders, and merchants coexisted in this space, capitalizing on nearby railroads and the Cooper River.

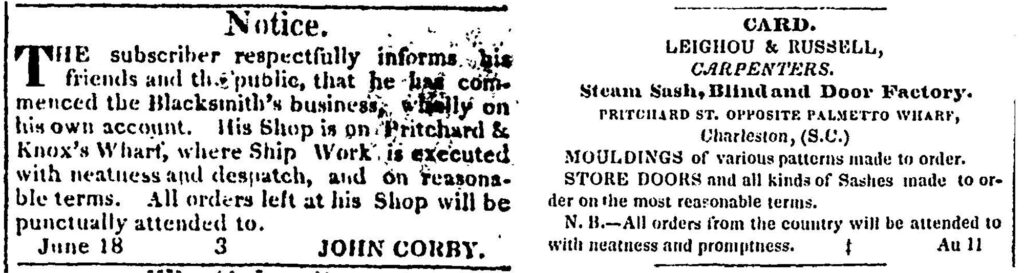

In the early 1800s, a blacksmith shop operated by John Corby was located on Knox’s Wharf. Union Cotton Compress opened adjacent to Union Wharf in 1845. Leighou & Russell Carpenters opened across from Palmetto Wharf on Pritchard Street in 1853.

Wilcox & Gibbs Guano Co. and Phosphate Works was located between Merchants’ and Palmetto wharves in the 1880s. In the 1890s, Consumers’ Coal Company and Pregnall’s Shipyard and Marine Railway were operating out of Merchants’ Wharf. By 1901, Riverside Iron Works had set up shop on Palmetto Wharf, specializing in fertilizer and phosphate machinery, as well as marine railway and shipbuilding. People could also purchase coal, iron, and building materials from Riverside Iron Works and other vendors on the waterfront.

The Bennett Rice Mill opened in 1844 adjacent to Bennett’s Wharves and was regarded as one of the finest examples of pre-Civil War industrial architecture in Charleston. After the economic decline following the Civil War and increased competition from other states effectively killed the rice industry in the Lowcountry, the facility ceased operation as a mill in 1911. The building briefly became a factory for Planters Peanut and Chocolate Company before closing permanently in the 1930s. A series of natural disasters, including a 1938 tornado that ripped off the building’s roof, compromised its structural integrity. Thanks to the effort of early preservationists, including the Preservation Society of Charleston, its façade still stands today as a symbol of the rice-cultivation industry and the system of enslaved labor that once fueled Charleston’s economy, now isolated in a sea of concrete.

Cultural Significance of Union Pier’s Historical Wharves

While trade and industry played a large role in shaping Union Pier’s waterfront, these historical wharves also contributed to Charleston’s rich cultural heritage.

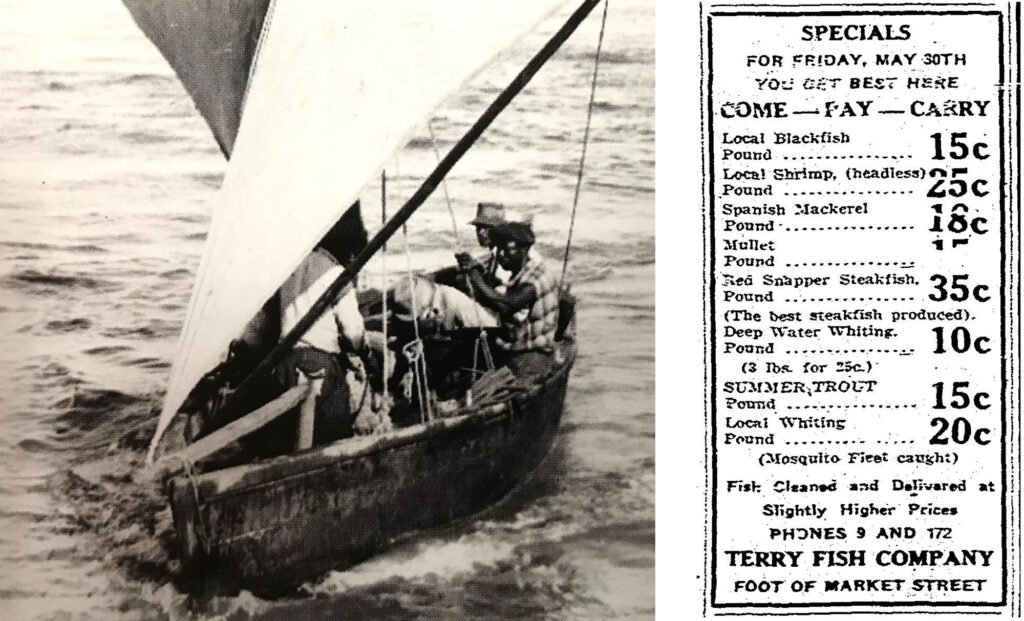

Charleston’s “Mosquito Fleet,” a small group of African American fishermen, formed well before the Civil War, and helped feed the city after the devastation of the war in the late 1860s. An 1885 newspaper article praised the Mosquito Fleet for being “steady, sober, industrious, and fearless,” in their dangerous line of work. They sailed their small fishing boats out of Fisherman’s Wharf, within Union Pier, at the foot of Market Street for decades. Immortalized by DuBose Heyward and George Gershwin’s opera, “Porgy and Bess,” the Mosquito Fleet had more than 100 men by the early 20th century. Many of these fishermen were part of multi-generational families and were decades-long veterans of the trade. Mosquito Fleet fishermen often sang distinctive songs as they brought in their hauls of blackfish, mullet, mackerel, red snapper, trout, whiting, shrimp, catfish, and more, to sell at Terry Fish Company and on Market Street. Through more than a century of hardship, including hurricanes, tornados, low rates of catch, dangerous gales, deadly seas, and more, members of the Mosquito Fleet persevered, making it a cultural touchstone long after its heyday. Eventually, the group disbanded in the 1970s.

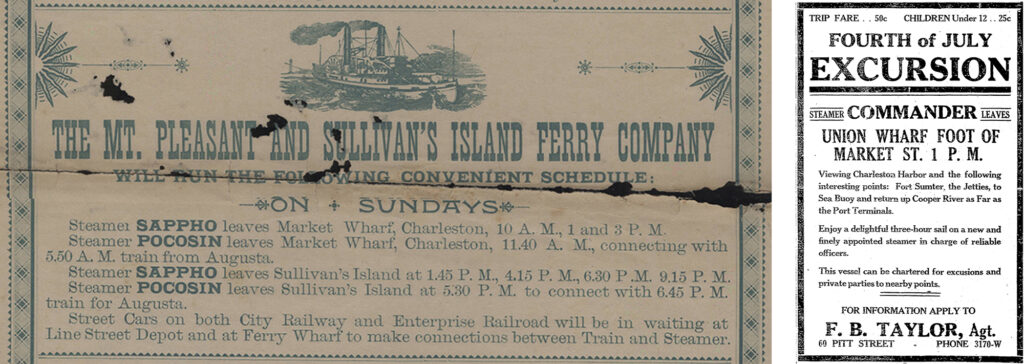

Now the backbone of Charleston’s economy, the tourism industry had its beginnings at the wharves, when Sullivan’s Island and Mt. Pleasant Ferry Company began operating out of Palmetto Wharf in 1849. This ferry company provided pleasure cruises and excursions to visitors and residents to Mt. Pleasant, Sullivan’s Island, Fort Sumter, and other waterfront destinations. In peak summer season, the ferry carried more than 7,000 passengers in a single day, and even assisted transporting people to safety during hurricanes. Pleasure cruises and ticketed outings open to the public also departed from Union Wharf at the turn of the 20th century.

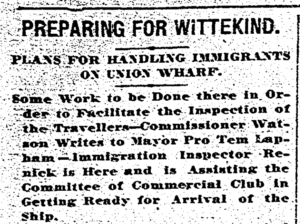

Immigrants from Europe and other parts of the world arrived in Charleston through Union Wharf and others nearby. One such vessel was a German ship, the Wittekind, on which 475 European immigrants arrived in 1906. It was the first immigrant ship to arrive in any South Atlantic port in 40 years, and was highly anticipated by locals, who came out in droves to welcome the newcomers.

As Union Pier expanded, historic city streets were absorbed, renamed, and sometimes lost altogether. “So It Be Lane” originally bordered the Union Pier property to the north, until the 1800s, when Laurens Street was extended and absorbed So It Be Lane. Marsh Street ran south from Laurens Street until 1986, when it was closed and abandoned as a public right-of-way by the City of Charleston at the request of the State Ports Authority.

Other historic features from these wharves were lost and forgotten through time, such as Lafitte’s Bell, the wharf bell of the Savannah Steam Packet Line located on Patton’s Wharf in the mid-1800s. It rang whenever the company’s two steamers, the Gordon and the Lucille, arrived and departed the wharf. During the throes of the Civil War in 1862, Lafitte’s Bell was removed and melted down to create ammunition for Confederate soldiers.

An Undeniable Impact on Charleston’s Culture

Present-day Union Pier isn’t much to look at – at least until it is redeveloped. The once-bustling urban industrial landscape that helped establish Charleston as the port city it is known as today has been largely forgotten and erased from public memory as historic structures were demolished, and the piers were consolidated and paved over. The courageous Mosquito Fleet fishermen, skilled tradespeople, and everyone who passed through and worked around these wharves had a significant impact on Charleston. The history of Union Pier is worth remembering and honoring as this major redevelopment project takes shape. So next time you hear Union Pier is a “blank slate,” remember, it’s just a slate that has been wiped clean.