Research and writing by Laurel M. Fay

Charleston’s waterfront landscape has changed drastically since the city’s founding in 1670. The downtown peninsula, once home to a network of inlets, creeks, and marshland, was slowly filled to expand buildable land area along the Charleston Harbor and Cooper and Ashley rivers.

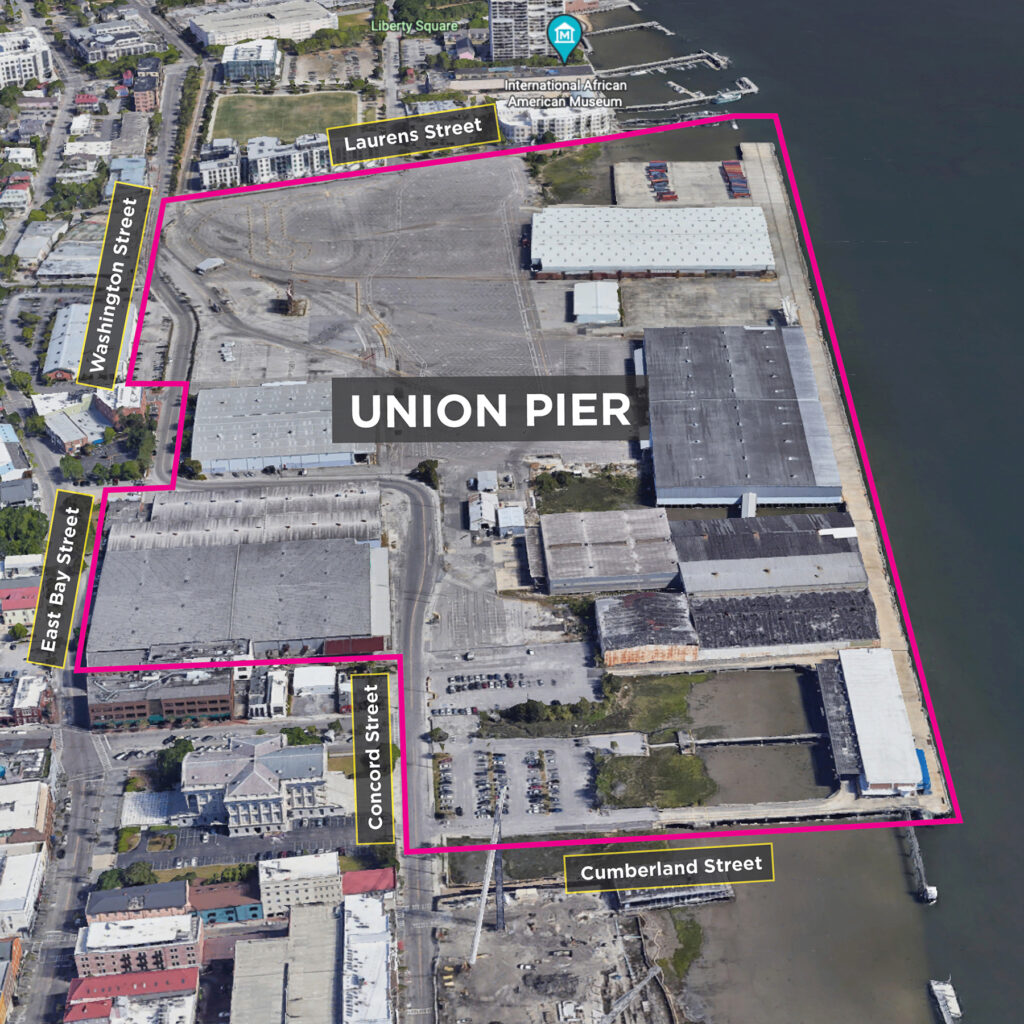

The Union Pier waterfront is no exception to this pattern of development. Wharves constructed in the 18th and 19th centuries extended out from high ground along the eastern edge of the peninsula, toward the Cooper River. These original modest, wooden-plank wharves were eventually replaced with large concrete piers stretching further into Charleston Harbor, increasing capacity to receive large cargo and passenger vessels. The 20th century brought about continued development of Union Pier through wharf expansion and property consolidation, furthered by economic growth in the post-WWII era.

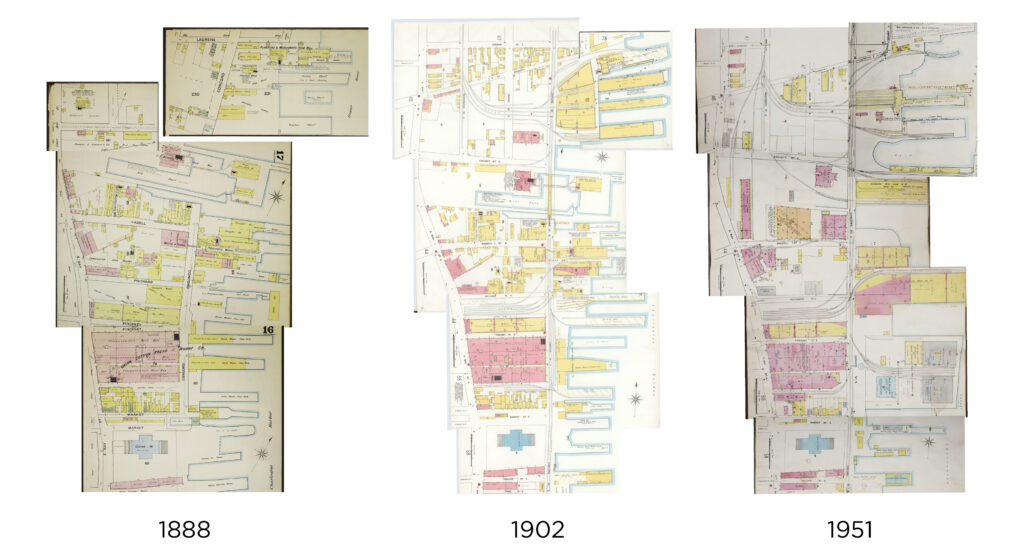

Union Pier’s ecological and land evolution patterns can be traced through historical maps:

Historical Maps Through Time

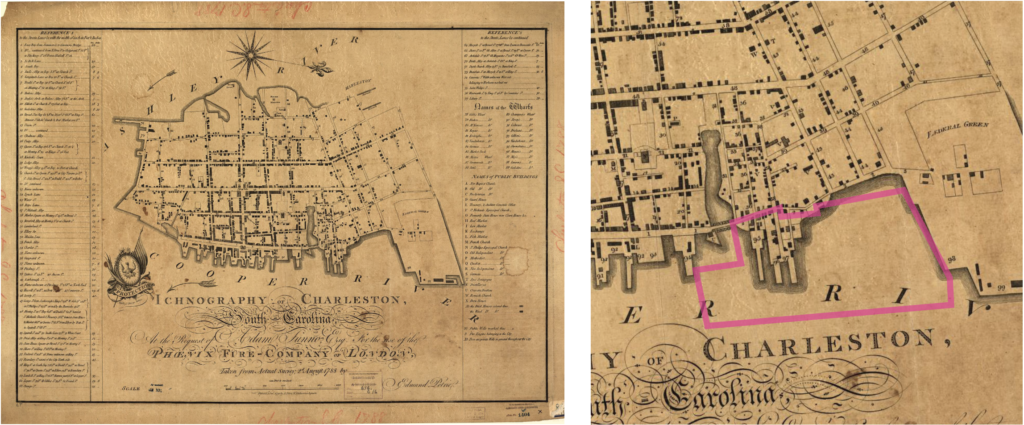

This early map of the Charleston peninsula from 1686 reveals that the throughfare we now call East Bay Street was the city’s first wharf, located adjacent to a sloping tidal mudflat. Due to this shallow topography, larger vessels utilized smaller boats known as “lighters” to unload their cargo and bring it into the wharf. Erosion was an issue during this period, and there were early attempts to combat this by fortifying and expanding the peninsula with fill.

This 1788 map of Charleston shows a few early landmarks on the eastern edge of the peninsula that are within the present-day Union Pier property, including Mey’s Wharf, Munro’s Wharf, and Shrewsbury’s Wharf, as well as a portion of Governor’s Bridge. To the south, the area that would become Market Street was still a waterway known as Daniel’s Creek at the time this map was drawn.

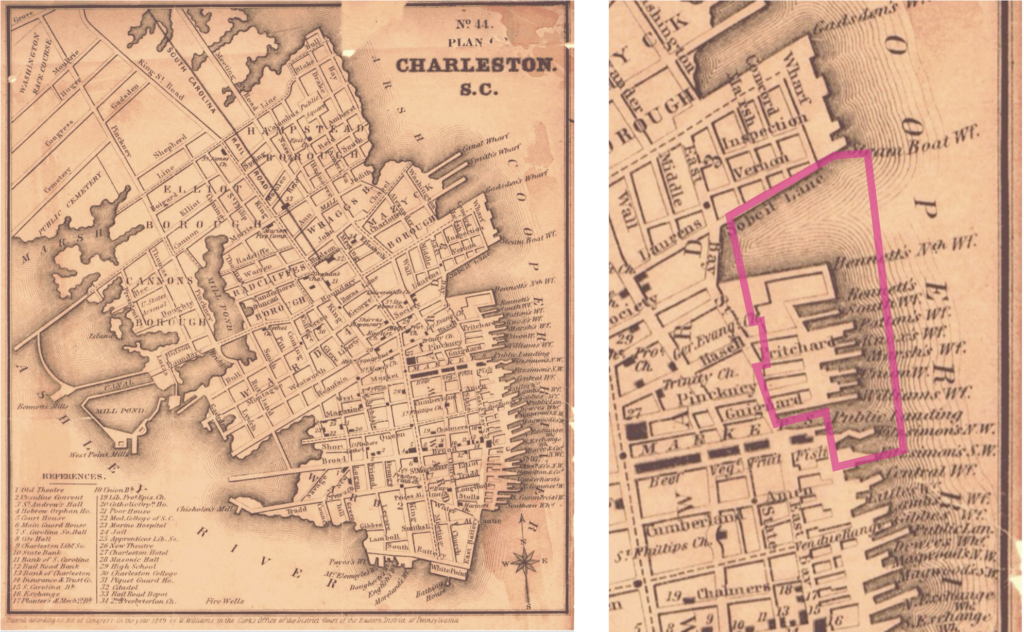

By 1849, the eastern part of the Charleston peninsula reflected a distinctive jagged edge made up of wooden wharves typically named for their owners, who were often wealthy merchants and businessmen. Smaller businesses and tenants set up shop at these landing areas, creating a diverse business district. There were eight wharves in the Union Pier property footprint: Bennett’s North and South Wharves, Patton’s Wharf, Knox’s Wharf, Marsh’s Wharf, Union Wharf, William’s Wharf, Fitzsimon’s Wharf, and a public landing.

In comparison with the 1788 map, the present-day Union Pier property has been further filled, and many more wharves have been constructed, creating fingers that extend into the Cooper River. Additionally, by this time, Market Street had been developed atop the filled-in Daniel’s Creek.

Union Wharf, originally established around 1842, was one of the busiest ports in Charleston. It was so successful that just four years later in 1846, it absorbed three adjacent ports – Knox’s, Marsh’s, and Williams’ wharves. With this expansion, it became known as Union Wharves #1-4. By the 1870s, the waterfront was dredged, allowing for much larger vessels to dock and unload right at these piers, increasing capacity and making domestic and international trade more efficient.

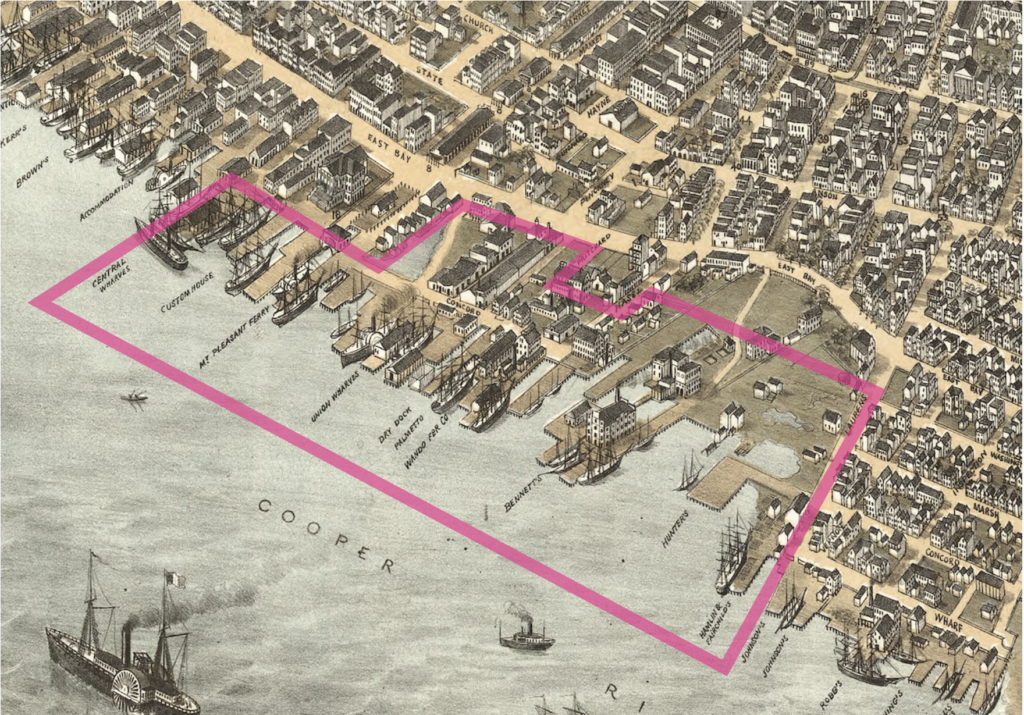

The Bird’s Eye View Map of Charleston from 1872 gives us a detailed interpretation of what this eastern wharf neighborhood looked like, from the scale of the vessels in port, to the manufacturing mills and collection of commercial and residential structures located within and adjacent to present-day Union Pier. Wharves changed hands and took on new names, reflective of their primary enterprise, such as Mt. Pleasant Ferry Wharf. The area that was once a marshy bay was completely filled in by this time.

The 1888 Sanborn map illustrates the effects of the Industrial Revolution on Charleston’s economy, with an increase in manufacturing, mills, and other large-scale businesses related to various industries. Ownership of these properties shifted from individuals to larger corporate entities who consolidated multiple parcels, capitalizing on access to the newly constructed and expanding railroad lines and Charleston Harbor.

The 1902 Sanborn map highlights the impact of the railroad on the Union Pier landscape. By the 1940s, Union Pier became one large wharf, controlled by the State Ports Authority, and by 1951, Sanborn Maps show consolidation of the previous finger-like wharves into larger concrete piers with wider berthing channels for modern ships. Together, these maps show the rapid development of Charleston’s ports in the post-industrial age as the city took steps to modernize to keep up with the fast-paced, globalizing post-World War II world.

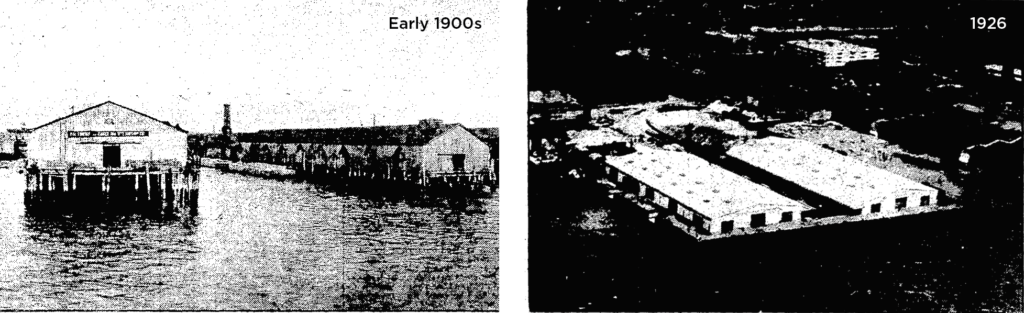

Union Pier’s Continued 20th Century Development

In 1922, the City of Charleston purchased Union Wharves and began making improvements to overhaul the facilities under the management of the Port Utilities Commission, which was established to manage the city’s waterfront properties. The four Union Wharves were consolidated into one large wharf and renamed Union Pier. Due to financial strain exacerbated by World War II, the Port Utilities Commission failed to turn a profit for the City, and the wharves fell into disrepair. In 1947, the newly formed South Carolina State Ports Authority took ownership of Union Pier and continued to build upon and expand its footprint, which continued into the late 20th century and resulted in the massive concrete pier we see today.

Building Upon Fill

Historical maps clearly show that the 70-acre Union Pier property was originally water or marshland that has been filled in over time – only about 36 acres, or 51%, is now high ground. The original wooden-plank, 19th century Union Wharf evolved to become today’s massive, concrete Union Pier. When this property is redeveloped, there could be hazardous results, as we have seen in other parts of the Charleston peninsula like the medical district, where flooding is a constant risk due to its position upon filled ground. Further, buildings as high as seven stories are proposed to be constructed here, which will drastically alter this neighborhood’s landscape.

Union Pier’s wharves and ecological landscape have historically been a microcosm of Charleston’s growth and development patterns, and its redevelopment will be the next phase of the evolution of our city’s waterfront landscape. Charlestonians don’t have to sit on the sidelines and watch as this project takes shape. We have a crucial opportunity to play an active role in shaping the future of Union Pier by advocating for the best possible designs, community benefits, and public space as part of this landmark, generation-defining project.