To fully understand Charleston’s history, it is critical to study and interpret the under-documented landscape of slavery and rice cultivation in the Lowcountry. That’s why the PSC is working alongside a dedicated task force of preservation professionals, historians, archeologists and conservationists to preserve threatened historic resources on Jehossee Island. Formerly one of the most productive rice plantations in the southeast and uninhabited for decades, Jehossee Island presents a rare and important opportunity to study and better understand tidal rice cultivation and the associated lifeways of enslaved Africans and African Americans in the Lowcountry in the antebellum period.

SITE CONTEXT AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Jehossee Island comprises 4,400 acres—3,700 of which are salt marsh and freshwater wetlands—situated roughly 25 miles southwest of Charleston on the South Edisto River. Since 1993, Jehossee has been managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the ACE Basin National Wildlife Refuge and is one of the largest undeveloped estuaries on the east coast. Today, Jehossee Island retains two intact historic structures: an overseer’s house, which was the residence of the white plantation overseer tasked with managing daily agricultural operations and the labor of the enslaved population; and a rice chimney, which was a crucial part of a complex system used for threshing harvested rice. Both structures are thought to date to the 1830s and are rare examples of their respective resource types.

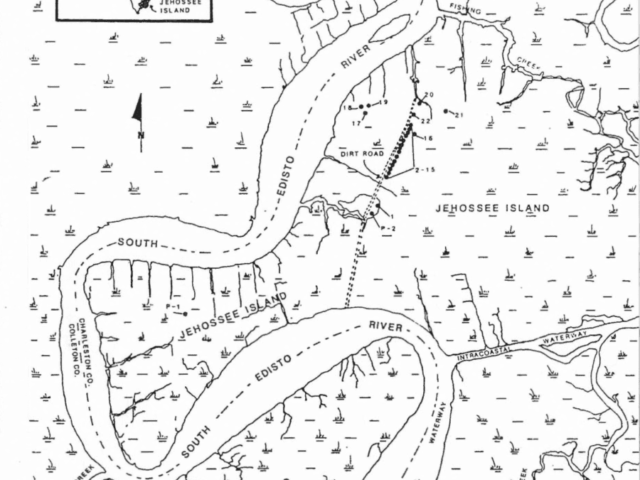

Top left: Map of resources identified by the S.C. Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology reconnaissance in 1986; top right: aerial view of the S. Edisto River near Jehossee Island; bottom: Overseer’s House and Rice Chimney in March, 2021, courtesy of Brent Fortenberry, Ph.D RPA.

The island’s history spans centuries with archaeological evidence of long-term Native American occupation long before European settlers and enslaved Africans and African Americans arrived c. 1685. Historical records indicate the island’s name evolved and varied throughout its history. On a map dated 1695, Jehossee is referred to as “Chebash,” which may have been a derivative of an earlier Native American name. By 1706, the island was referred to as “Johoowa,” then “Johassee” by the time of the Yemassee War in 1715, eventually transitioning to “Jehossa,” and finally “Jehossee” by the end of the 18th century.[1]

Jehossee was first recorded as a working rice plantation in the 1760s, corresponding with the period of time when rice was on the rise as a major export industry in the Carolinas. Jehossee was solidified as a productive rice plantation under the long-term ownership of two of the most affluent and politically-powerful families in the Lowcountry’s history: the Draytons and the Aikens.

Jehossee was owned by the Drayton family from 1776 until 1824, and was then property of Governor William Aiken and his descendants from the 1830s until ownership was transferred to the USFWS in the 1990s. Charles Drayton, who also owned Drayton Hall Plantation, wrote extensively about day-to-day management of Jehossee in the late 18th and early 19th century in his diaries, although he likely spent little time there. Drayton’s entries provide the most detailed, surviving accounts of daily life on Jehossee. For example, we know from his writings that, in addition to rice, enslaved people on Jehossee grew corn, potatoes, indigo, and cotton.[2]

Drayton’s accounts also provide sobering insight into systems of power on Jehossee as they relate to the historic landscape. In early 1800, Drayton documented complaints from the enslaved population of poor treatment from the overseer, Thomas Merchant. After dismissing these complaints, Drayton received a letter later that year from an Edisto Island planter reporting the death of overseer Thomas Merchant at Jehossee. Little more is known beyond Drayton’s self-reported deportation of several enslaved people from Jehossee to Edisto “by warrant on suspicion.”[3] However, this event offers an important glimpse into life on Jehossee and provides supporting evidence that enslaved Africans and African Americans, even those living in highly isolated settings like Jehossee, were not passive victims of the horrors of slavery, but often engaged in various forms of resistance.

Charles Drayton also built the earliest known plantation house on the island, which was replaced by a later complex under the subsequent ownership of the Aiken family. Neither the Drayton nor the Aiken plantation houses survive; however, historical accounts, foundation remnants, and other artifacts provide insight to the buildings’ construction, materials, and form.

Historical records suggest the Drayton house was “spartan” and rarely visited, and may have been built on a tabby foundation repurposed in the later construction of the Aiken house. The Aiken plantation house, which survived until being destroyed by a fire in the late 19th century, is thought to have been higher style than its predecessor, and likely more frequently used. The Aiken house was a square structure, likely clad in weatherboard siding, with a hipped, wood shingle roof, and a full-facade porch on the south elevation. The main house complex included five additional outbuildings, and a garden.[4]

William Aiken, the 61st Governor of South Carolina (1844-1846), purchased the core tract of Jehossee in 1830, later expanding it to its current size. By 1850, Aiken had brought 1,500 acres of rice land under tidal cultivation, a staggering area that represented nearly twice the acreage of the next largest rice plantation in the South at the time, dependent upon the labor of one of the largest enslaved populations on record.[5]

RICE CULTIVATION AND THE LANDSCAPE OF SLAVERY

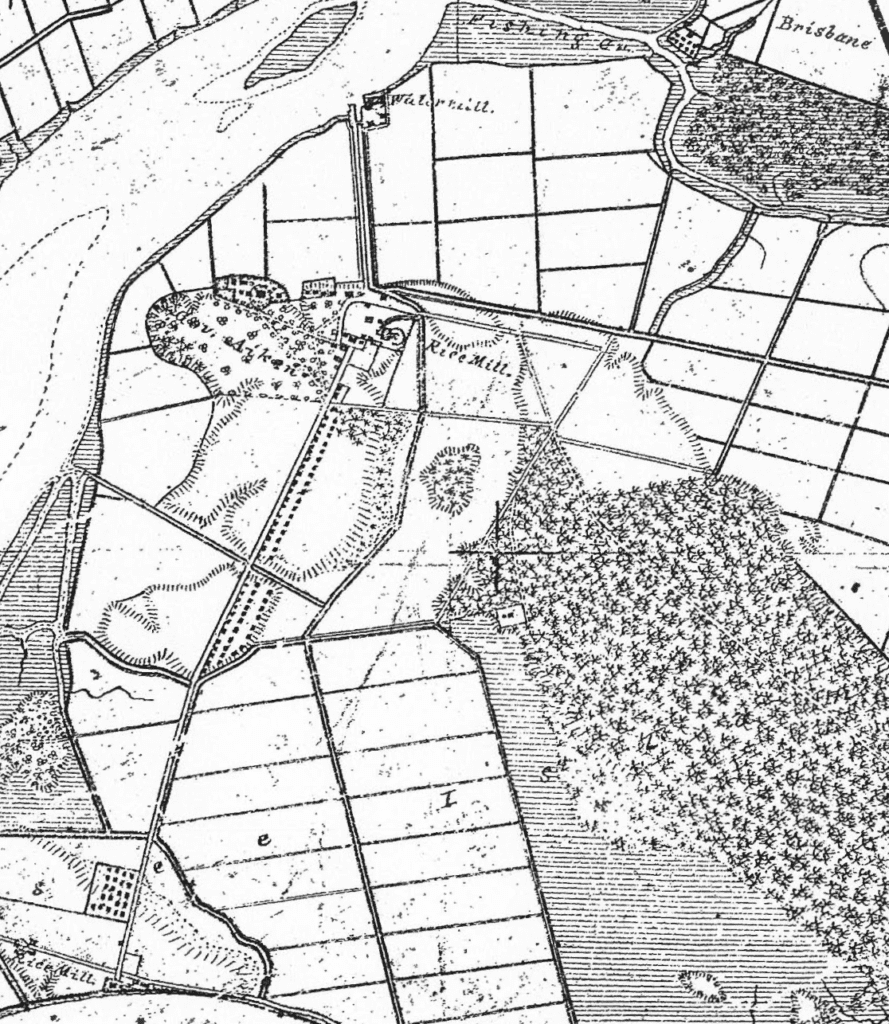

US Coast Survey, 1856-57

Highly labor intensive, tidal rice cultivation relied on trunks to direct water flow from freshwater rivers to rice fields via canals painstakingly forged by enslaved workers—a truly herculean task. Rice production and processing at this level necessitated a large and complex infrastructural system including dikes, trunks, and canals, many of which remain largely intact on Jehossee today. Former rice fields and systems have been adapted as managed impoundments by the USFWS for wildlife and water management on the island. The continued existence of the 19th century historic agricultural landscape and infrastructure is dependent upon routine maintenance and frequent rehabilitation.

Jehossee was the pinnacle of tidal rice production in the Lowcountry in the 19th century, the success of which was built on the backs of one of the largest enslaved populations in the South. At peak cultivation between the 1830s and 1860s, an estimated 700-900 enslaved persons lived and labored on Jehossee Island.[6]

19th century written accounts and a site plan completed as part of the 1856-1857 U.S. Coast Survey indicate the presence of an extensive village built by and for Jehossee’s enslaved population, including a recorded 84 wood frame houses, a church, a hospital, a store, and an overseer’s house, among other industrial structures associated with rice cultivation.[7]

Shown on the map above, the extensive, double-to-triple row of structures comprising the enslaved village is a rarity. Unfortunately, only brick from former chimneys remain as above-ground evidence of this settlement, pointing to the significant potential for archaeological study to better understand the lifeways and resources of Jehossee Island’s enslaved population.

ONGOING PRESERVATION EFFORTS

Left: double oak allee on Jehossee Island; right: Rice Chimney site, courtesy of PSC Staff.

Jehossee Island has been uninhabited and relatively undisturbed for more than half a century. The USFWS has been a responsible steward of this landscape for nearly 30 years, but by the time the island came under federal ownership in 1993, the Overseer’s House and Rice Chimney had long been out of use, already the victim of decades of neglect and exposure to harsh elements. The vulnerability of Jehossee’s historic resources has been exacerbated by successive and worsening hurricane seasons and the ever-increasing threat of sea level rise, ultimately leading to the launch of a coordinated effort to ensure their preservation.

In 2018, the Preservation Society and our partners at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the ACE Basin Task Force, Drayton Hall, the Charleston Museum, and Historic Charleston Foundation joined forces to identify preservation priorities and necessary funding, beginning with the Overseer’s House and Rice Chimney site.

Post-hurricane federal funding following the series of storm events that impacted the Lowcountry from 2015 to 2018 was key in providing for the large-scale clean-up of the site, protecting the house and chimney from further damage from encroaching vegetation.

Next, the group engaged historic preservation and vernacular architecture professor and scholar Brent R. Fortenberry, PhD of Tulane’s School of Architecture to spearhead documentation efforts. Dr. Fortenberry specializes in the vernacular architecture of the British Atlantic world and digital documentation of associated resources.

Digital documentation of the Jehossee Island Overseer’s House courtesy of Brent Fortenberry, Ph.D RPA.

In March 2021, a field team comprised of Dr. Fortenberry, restoration contractors Thomas Graham III and Beekman Webb, and structural engineer John Moore, undertook a comprehensive documentation and conditions assessment on Jehossee Island. The team completed analog and digital documentation of the Overseer’s House and Rice Chimney site and a preliminary GNSS survey of the former Drayton-Aiken Plantation House complex.

Information gathered on-site directly informed a subsequent submittal to the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) outlining a plan for stabilization and phased rehabilitation of the Overseer’s House. With SHPO approval and the support of generous donors, the project team successfully stabilized and began rehabilitation of the c. 1830s Overseer’s House in fall 2021. To date, the scope of work has included major foundation and siding repairs, repointing of chimneys, and in-kind replacement of the failing roof and window sashes.

NEXT STEPS

Left: documentation of brick ruins at the former rice mill site on Jehossee Island, right:aerial view of partially flooded former rice fields, drone photography courtesy of Brent Fortenberry, Ph.D RPA.

Beyond rehabilitation of the Overseer’s House and Rice Chimney complex, there is tremendous opportunity for site survey, laser scanning, and archaeological study across Jehossee Island’s sprawling landscape. This progressive analysis has the potential to reveal new insight into the daily lives and material culture of enslaved Africans and African Americans, whose lives are severely underrepresented in the interpretation of plantation sites across the Lowcountry and beyond. We look forward to sharing more on this project as documentation and preservation efforts continue. To learn more about Jehossee Island, please utilize the resources below, or email the Advocacy team at advocacy@preservationsociety.org. To support the PSC’s preservation and research initiatives, you can give a gift online or contact the Advancement Department at advancement@preservationsociety.org.

RESOURCES

To learn more about the history and landscape of Jehossee Island, the PSC recommends the following resources:

Archaeological and Historical Investigations of Jehossee Island, Charleston County, South Carolina, Chicora Foundation, Inc., 2002.

Imagining Jehossee Island Rice Plantation Today, International Journal of Heritage Studies, Antoinette T. Jackson, Ph.D., 2008.

Plantations, Planning & Patterns: An Analysis of Landscapes of Surveillance on Rice Plantations in the Ace Basin, SC, 1800-1867, Clemson University Tiger Prints, Sada Stewart, 2019

[1] Chicora Foundation, Archaeological and Historical Investigations of Jehossee Island, Charleston County, South Carolina, 2002, p. 33 (Thorton-Morden map showing “Chebash” and vicinity of Jehossee Island, 1695).

[2] Chicora, p. 53.

[3] Drayton Hall Interiors 20(2), Research News: Learning from Jehossee, Summer, 2001. (Chicora, p. 53)

[4] Chicora, p. 55, 162.

[5] Chicora, p. 201.

[6] Dr. Antoinette T. Jackson, Imagining Jehossee Island Rice Plantation Today, International Journal of Heritage Studies, University of South Florida, 2008, p. 141.

[7] 1856-1857 U.S. Coast Survey