Constructed in 1931 to house national “five and dime” retailer, S.H. Kress & Co., the Kress Building at 281-283 King Street is known today as the site of one of the most impactful civil rights protests in the southeast. The three-story, yellow brick department store is one of Charleston’s most notable Art Deco style buildings, designed by the Kress company’s preeminent in-house architect, Edward Sibbert. Founded in 1896, S.H. Kress & Co. operated a chain of “five and dime” stores across the country, notorious for excluding African American patrons from its lunch counters. Throughout the South, segregated lunch counters in department stores like S.H Kress & Co. became principal platforms for peaceful protest against segregation during the 1950s and 1960s.[1]

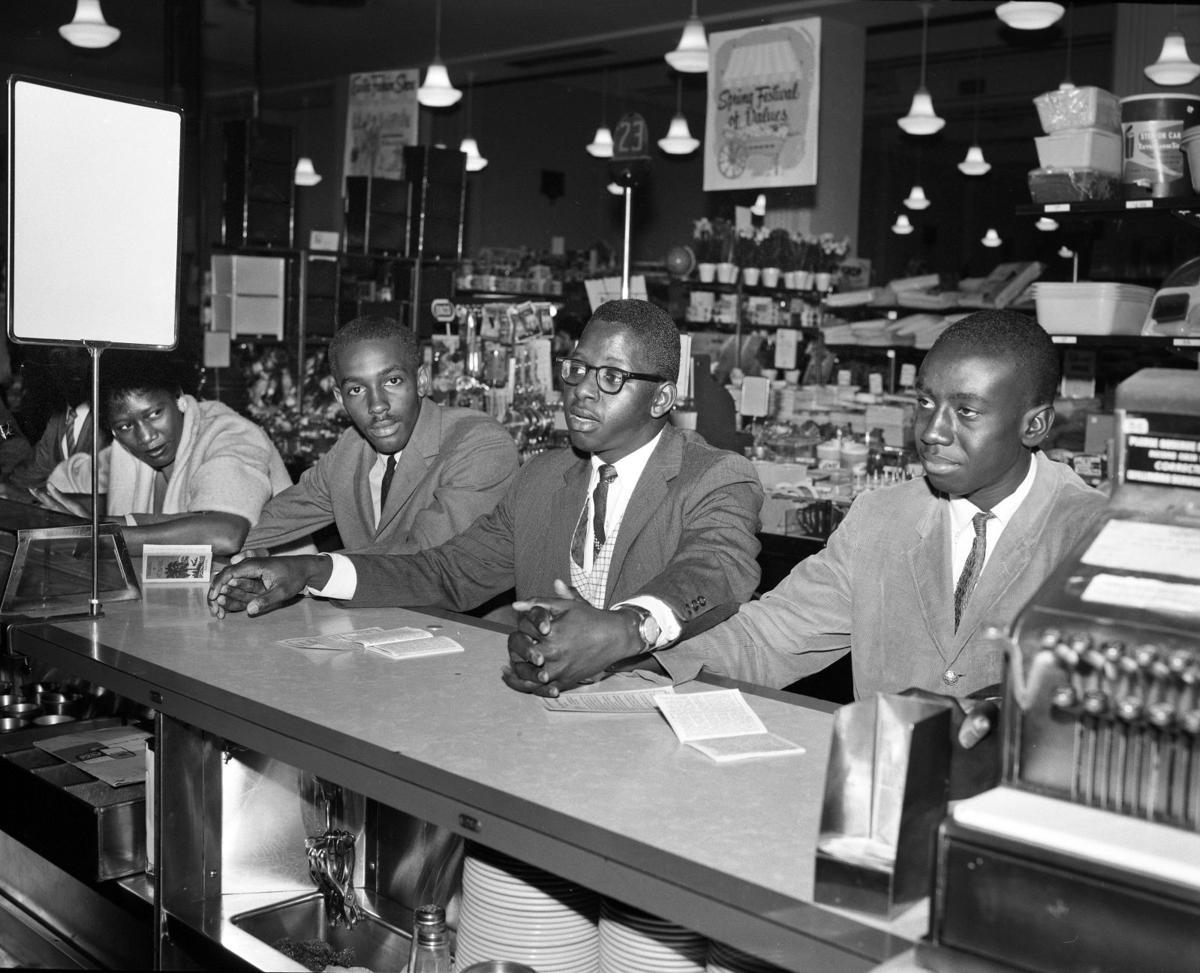

On April 1, 1960, 24 students from the all-African American Burke High School quietly marched into the Kress Building on King Street and sat down at the lunch counter. Inspired by the student-led Greensboro, N.C. sit-in that took place on February 1 of that year, the Burke High School students met regularly at Emanuel A.M.E Church for months in advance of the Kress sit-in to plan and train for the non-violent demonstration.[2] Upon seating themselves at the lunch counter, the students were immediately refused service and asked to leave, but they peacefully resisted. In response, the manager removed the seats from any empty stools, and a waitress poured ammonia on the lunch counter.[3] When these efforts failed to deter the students, management falsely claimed that there was a bomb in the building, yet the students still refused to leave. After five hours of peaceful protest, the 24 demonstrators were ultimately arrested on trespassing charges when they refused to heed Charleston Police Chief William F. Kelly’s order to vacate the building.[4] Just hours later, local branch president of the NAACP, J. Arthur Brown, posted bail for the students, including his own daughter Minerva Brown. The student demonstrators were later represented in court by prominent Civil Rights attorney Matthew Perry. While the South Carolina Supreme Court ultimately decided that charges should not be pursued, the impact of the Kress Building sit-in had a major impact on the future of civil rights activism in Charleston.

This act of civil disobedience contributed significantly to the trajectory of organized, non-violent civil rights demonstrations in Charleston throughout the 1960s, known as the “Charleston Movement.”[5] During the Movement, there were several additional sit-ins at the Kress Building, including an attempted sit-in on July 25, 1960 that was prevented by Kress employees, and two successful demonstrations that took place on June 10 and June 11, 1963. Even after the passage of the national Civil Rights Act in 1964, which made segregation in public places illegal, the struggle against the firmly rooted system of racial oppression solidified under Jim Crow society continued for years to come.[6] The Kress sit-in of April 1, 1960, sparked lasting momentum in local civil rights activism and is recognized today as a significant moment of the American Civil Rights Movement.[7]

Student demonstrators, aged 16-20, included John Bailey (17), James Gilbert Blake (17), Jenniesse Blake (16), Andrew Brown (16), Deloris Brown (17), Minerva Brown (16), Charles Butler (17), Mitchell Christopher (18), Allen Coley (17), Corelius Fludd (18), Harvey Gantt (17), Joseph Gerideau (19), Kennett Andrew German (18), Cecile Gordon (18), Annette Graham (17), Alfred Hamilton (16), Caroline Jenkins (17), Francis Johnson (18), Joseph Jones (18), Alvin Delford Latten (17), Verna Jean McNeil (16), David Paul Richardson (17), Arthur Singleton (20), and Fred Smalls (17).[8]

Many went on to make further impact in the Civil Rights Movement through continued activism. Notably, participant Harvey Gantt became the first African American student admitted to a public South Carolina university in 1963, and the first African American mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina in 1984.[9] Minerva Brown and her sister Millicent Brown were key plaintiffs in a high-profile lawsuit against Charleston County School District 20 challenging the District’s refusal to desegregate even after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The case was filed under Minerva’s name in 1959, but the decision that Charleston County Schools must desegregate was not handed down until 1963, by which time Minerva had graduated high school and Millicent’s name replaced hers as the lead plaintiff in Millicent Brown et al v. Charleston County School Board, District 20.[10]

Click the images below to explore the Kress building sit-in gallery.

Image 1: Historic marker highlighting the history of the Kress building sit-in, erected by the Preservation Society of Charleston in 2013. Courtesy of the Preservation Society of Charleston.

Image 2: Burke High School students seated at the Kress lunch counter on April 1, 1960. Courtesy of the Post and Courier.

Image 3: The Kress building located at 281-283 King Street in Charleston, South Carolina, 2019. Courtesy of the Preservation Society of Charleston.

Image 4: Burke High School students seated at the Kress lunch counter on April 1, 1960. Courtesy of the Post and Courier.

Image 5: Postcard depicting King Street looking north from Wentworth Street featuring the Kress Building second from left, ca.1930. Courtesy of the Historic Charleston Foundation.

Image 6: Aerial Image of the 24 Burke High School students seated at the Kress lunch counter prior to their arrest. Courtesy of the Post and Courier.

[1] William D Smyth, “Segregation in Charleston in the 1950s: A Decade of Transition.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 92, no. 2 (1991): 121–123; William Lewis Burke and Belinda Gergel, eds. Matthew J. Perry: The Man, His Times, and His Legacy. Columbia: Univ of South Carolina Press, 2004, 230; Glenn Robertson, “Negroes Here Asked to Boycott 3 Stores,” The News and Courier, April 7, 1960.

[2]Adam Parker, “The Sit-in That Changed Charleston” Post and Courier, Online edition; Jon Hale, “‘The Fight Was Instilled In Us’: High School Activism And The Civil Rights Movement In Charleston,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 114, no. 1 (2013): 4–28.

[3] Minerva Brown King, interview by Historic Charleston Foundation, Tangled Roots, March 5, 2020, video, 4:27, https://vimeo.com/395721178.

[4] Millicent Ellison Brown, “Civil Rights Activism in Charleston, South Carolina, 1940-1970.” Florida State University, 1997, 166-194; “24 Arrested Here in Demonstration.” The News and Courier. April 2, 1960, sec. A pg. 8. “Negro Youth Stage Sitdown at Counter,” Charleston Evening Post, April 1, 1960, sec. A pg. 1; Stephen O’Neill, From the Shadow of Slavery: The Civil Rights Years in Charleston, Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1994, 198-200; Parker, “The Sit-in That Changed Charleston.”

[5] “Commemorating South Carolina’s Civil Rights History,” https://discoversouthcarolina.com/articles/com memorating-south-carolinas-civil-rights-history; “Charleston Demonstrations Go To The Lunch Counters,” The Times and Democrat, June 11, 1963; “3 Charleston Stores Are Targets of Sit-Ins,” The Greenville News, June 12, 1963.

[6] The Education of Harvey Gantt, Part 2 – The Road To Clemson. Accessed June 6, 2019; Harvey Gantt: Episode 1: The Young Pioneer | Season 2016 Episode 2501 | Biographical Conversations With… Accessed June 6, 2019; Smyth, “Segregation in Charleston in the 1950s”; Burke and Gergel, Matthew J. Perry, 186-187; Brown, “Civil Rights Activism in Charleston, South Carolina,” 166-194; “Negro Youth Stage Sitdown at Counter”; “24 Arrested Here in Demonstration.” Smyth, “Segregation in Charleston in the 1950s,” 100.

[7] Educating South Carolina. “Educating South Carolina: Burke Students Set Examples, Changed History.” Educating South Carolina(blog), April 4, 2012; Smyth, “Segregation in Charleston in the 1950s”; Millicent Ellison Brown, “Civil Rights Activism in Charleston, South Carolina, 1940-1970,” 166-194; “24 Arrested Here in Demonstration”; “Negro Youth Stage Sitdown at Counter”; O’Neill, From the Shadow of Slavery, 198-200; Parker, “The Sit-in That Changed Charleston.”

[8]“24 Arrested Here in Demonstration.”

[9] Harvey Gantt: Episode 2: Mayor of Charlotte | Season 2016 Episode 2502 | Biographical Conversations With… Accessed June 21, 2019; Robertson, “Negroes Here Asked to Boycott 3 Stores,”; Parker, “The Sit-in That Changed Charleston.”

[10] Millicent Brown, Jon Hale, Somebody Had To Do It: First Children in School Desegregation, Desegregation in Charleston, Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, http://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/somebody_had_to_do_it

<!– Today occupied by a small playground, the southwest corner of Beaufain and Wilson Streets was once the site of the first church building to house Calvary Episcopal Church, the oldest African American Episcopal congregation in Charleston.[1] Calvary Church, now located at 106 Line Street, was established in 1847 by the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina for the religious instruction of free and enslaved African Americans in Charleston, separate from white parishioners. For nearly a century, Calvary’s original church building served as an important spiritual center for much of Charleston’s Black community. However, in 1961, Calvary Church was demolished as a result of redevelopment pressure that disproportionately impacted historically Black neighborhoods and institutions in Charleston during the mid-20th century.

Constructed in the Early Classical Revival Style in 1849, the design of Calvary Church represented a combination of Greek and Roman influences.[2] Built of brick with a white stucco finish, the one-story church building accommodated up to 400 people.[3] The front façade featured a broad entablature and pediment over a paneled door with an elliptical fanlight flanked on each side by Tuscan pilasters and semicircular niches. Full-height, triple-hung windows spanned the east and west facades, with a semicircular apse located at the rear. [4]

The congregation faced one of its earliest, and most severe trials before the construction of the church was complete. On July 13, 1849, a riot began at the Charleston Work House, a notorious penal institution utilized primarily for the punishment of enslaved people, located less than one block away from Calvary. Led by an enslaved man named Nicholas, approximately 37 prisoners temporarily escaped the Work House, inciting the panic and anger of the white community.[5] The day following the riot, a mob of white Charlestonians assembled in an attempt to destroy the church in retaliation; while the Calvary Church congregation was closely surveilled by an all-white clergy, many in the community viewed the founding of Calvary Church as a dangerous and unprecedented allowance of Black independence, and sought its destruction.[6] Notably, violence was quelled by prominent local attorney James L. Petigru, known for openly representing free people of color, who convinced the mob not to destroy the church.[7]

On December 23, 1849, Calvary Church was consecrated by Rev. Christopher Gadsden, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of SC.[8] By the end of the following decade, Calvary had one of the largest Sunday School programs in the city, and eventually claimed the membership of some of Charleston’s most prominent African American citizens, like Justice Jonathan Jasper Wright. Calvary’s growth continued into the early 20th century. By 1940, however, neighborhood demographics in the area now known as Harleston Village were shifting toward a predominantly white population, resulting in the loss of congregants at Calvary. Simultaneously, the Housing Authority of Charleston began pressuring the congregation to relocate as the newly-constructed, white, housing project, Robert Mills Manor, surrounded the church on all sides.[9] As a result, the congregation ultimately purchased a piece of property at 106 Line Street as the new location for the church, where services are still held today. On November 25, 1940, the last service was held at Calvary Church on Beaufain Street.[10]

Following relocation, old Calvary Church stood vacant for 20 years until the Housing Authority submitted a request for demolition on April 29, 1960. In spite of community opposition to the request, all attempts to save the Church from demolition ultimately failed and after being deemed unsafe, Calvary was razed in August, 1961.[11]

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”12″ display=”pro_tile”]

[1] K. R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church: Extension of Robert Mills Manor Forces Negro Episcopal Congregation to Vacate 90-Year-Old Building,” The Charleston News and Courier, July 22, 1940.

[2] Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile,” n.d., http://www.episcopalchurchsc.org/uploads /1/2/9/8/12989303/calvary_episcopal_church_profile.pdf.; K. R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church.”

[3] “Calvary Church, Charleston, in Beaufain-Street.,” Charleston Gospel Messenger and Protestant Episcopal Register (1842-1853), January 1850.; Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”

[4] Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile,” n.d., http://www.episcopalchurchsc.org/uploads /1/2/9/8/12989303/calvary_episcopal_church_profile.pdf.; K. R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church.”

[5] Bernard E. Powers, Black Charlestonians, 17.

[6] Bernard E. Powers, Black Charlestonians, 17.; Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”; K.R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church.”; Robert F. Durden, “The Establishment of Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church for Negroes in Charleston,” 77.

[7] Bernard E. Powers, Black Charlestonians, 17.; Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”; K.R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church.”; Robert F. Durden, “The Establishment of Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church for Negroes in Charleston,” 77.

[8] Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”

[9] Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”; Edward G. Lilly, ed., Historic Churches of Charleston, South Carolina, 131.; K.R., “Do You Know Your South Carolina: Calvary Church.”; “71 Beaufain Street (Calvary Chapel) – Property File,” Charleston Past Perfect, accessed June 9, 2020, https://charleston.pastperfectonline.com/archive/2A7D91C8-2A24-473F-AB0F-052572729247.

[10] Calvary Episcopal Church, “Calvary Episcopal Church Profile.”; Edward G. Lilly, ed., Historic Churches of Charleston, South Carolina, 131.

[11] Barbara J. Stambaugh, “Calvary Chapel Demolition Ordered by City Officials: Attempts to Preserve Church Fail.”

–>