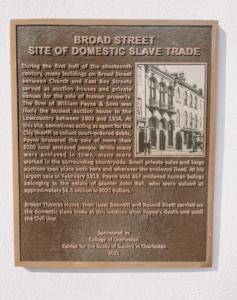

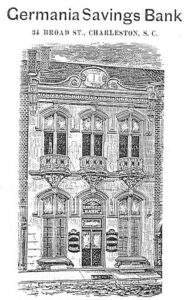

Between 1803 and 1834, William Payne & Sons, located at present-day 34 Broad Street, was one of the busiest auction houses in Charleston’s domestic slave trade. The Neoclassical style building that occupies the site today was constructed in 1962 for First Federal Savings and Loan Association, now South State Bank, and replaced the two demolished historic structures at 32-34 Broad Street where it is estimated that nearly 10,000 enslaved people of African descent were bought and sold as property.

As a port city, Charleston was a central location in the international slave trade, with approximately 200,000 enslaved people transported through the Port of Charleston from 1670 to 1808.[1] That total accounts for an estimated 51% of enslaved Africans who came to the United States, more than any other mainland colony.[2] On January 1st, 1808, Congress enacted legislation to prohibit the importation of enslaved people in the United States.[3] While this act ended American participation in the international slave trade, domestic trade continued in the United States until the abolition of slavery in 1865.

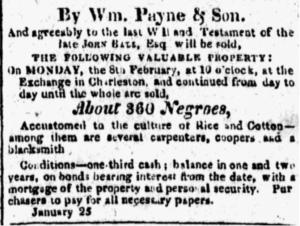

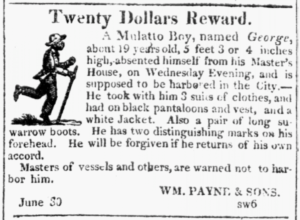

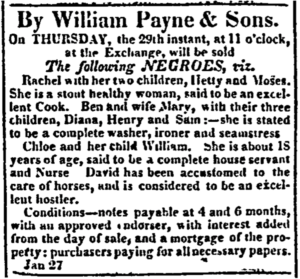

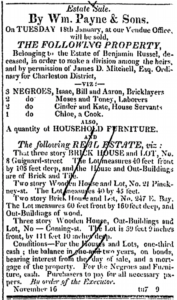

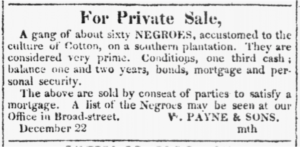

In Charleston, enslaved people were imported, bought, and sold at high-profile waterfront locations, such as the Exchange and Custom House at East Bay and Broad Streets and Gadsden’s Wharf further north on the banks of Cooper River. During the colonial era, the power to sell goods by auction was concentrated in one official, a Vendue Master, who was appointed by the governor.[4] The Vendue Master and appointed deputies were responsible for handling all sales by vendue (auction) in Charleston.[5] After the legal authority to conduct auctions in Charleston was decentralized in 1779, the government began to issue licenses to auctioneers, leading to the rise of a new class of businessmen who specialized in marketing, selling, and transporting of enslaved people on behalf of owners.[6] These agents were often called brokers, auctioneers, vendue masters, or traders, and advertised their auctions in local newspapers.[7] Rather than receiving a salary, auctioneers would receive a percentage of all transactions, and fees for incidental charges related to housing, feeding, and clothing the enslaved people they sold.[8] Many auctioneers secured office spaces near key commercial locations. William Payne & Sons, for instance, was located one block to the west of the Exchange Building on Broad Street.[9] The business also had a smaller vendue office at the northeast corner of East Bay and Gillon Streets for large public auctions.

The William Payne & Sons auction house began operation in 1803, after Irish immigrant William Payne expanded his estate sale brokerage, debt collections, and tax delinquency businesses to include the slave trade.[10] Ongoing research indicates Payne brokered the sale of more than 9,200 enslaved people during the first three decades of the 19th century. After the death of William Payne in 1834, his son Josiah Smith Payne continued the sale of enslaved people despite a gradual, local transition from a public-facing auction environment on the streets of Charleston to more private viewings and sales of enslaved people behind closed doors. In 1856, a city ordinance made public sale of enslaved people “or any other commodity” illegal in public spaces, which remained on the books until the abolition of slavery in 1865.[11]

Interpretation of this site, furthered by the installation of a historic marker in 2021, allows for an expanded view of the presence of the slave trade in Charleston beyond traditionally-accepted locations. Director of the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, Dr. Bernard Powers, explains: “This research is further compelling evidence that we are still daily learning how and the extent to which pre-Civil War Charleston was a city so organically and thoroughly entwined with slavery.”[12]

The research on the domestic slave trade of Charleston is an ongoing project of Margaret Seidler, 4th great-granddaughter of William Payne, and the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery. Further investigation of historical newspapers, tax records, and business transactions will continue to contribute to modern understanding of the lived experiences of enslaved people in Charleston, and the role of institutions like the auction house of William Payne & Sons and the many other nearby auction houses.

In March 2024, Margaret Seidler published a book, “Payne-ful” Business: Charleston’s Journey to Truth, chronicling her efforts to process her genealogical past and support ongoing work to reconcile Charleston with its slave-based economy and modern consequences. Building on extensive research, Seidler discusses the realities of Charleston’s racial history, while highlighting the historians, journalists, and community members who work to illuminate these truths.

[1] “Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.” Slave Voyages. Rice University. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database.

[2] “Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.” Slave Voyages.

[3] “The Slave Trade.” National Archives and Records Administration, January 7, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/slave-trade.html.

[4] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine. Charleston County Public Library, January 29, 2021. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/street-auctions-and-slave-marts-antebellum-charleston.

[5] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine.

[6] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine.

[7] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine.

[8] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine.

[9] Butler, Nic. “Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston.” Charleston Time Machine.

[10] Hawes, Jennifer Berry, and Brad Nettles. “A White Woman Bridged the Races. Then She Found Slave Traffickers in Her Family.” Post and Courier, June 14, 2021. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/a-white-woman-bridged-the-races-then-she-found-slave-traffickers-in-her-family/article_7b395e16-3dc8-11e8-aa1e-7308ef7578b4.html.

[11] “An Ordinance to prevent sales at auction in the streets and places surrounding the Custom House,” ratified on 15 April 1856, in John Horsey, comp., Ordinances of the City of Charleston from the 14th September, 1854, to the 1st December, 1859; and the Acts of the General assembly Relating to the City Council . . . and the City . . . during the Same Period (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Co., 1859), 25

[12] Dr. Bernard Powers, Director of the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, 2022.

![34 Broad Street_Sanborn Map comparison_1884 and 1888_updated[36]](https://www.preservationsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/34-Broad-Street_Sanborn-Map-comparison_1884-and-1888_updated36-300x273.png)

![34 Broad Street_South State Bank_2023 Google Earth[10] copy](https://www.preservationsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/34-Broad-Street_South-State-Bank_2023-Google-Earth10-copy-300x239.png)