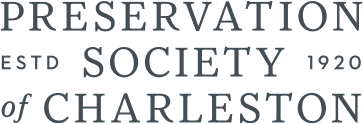

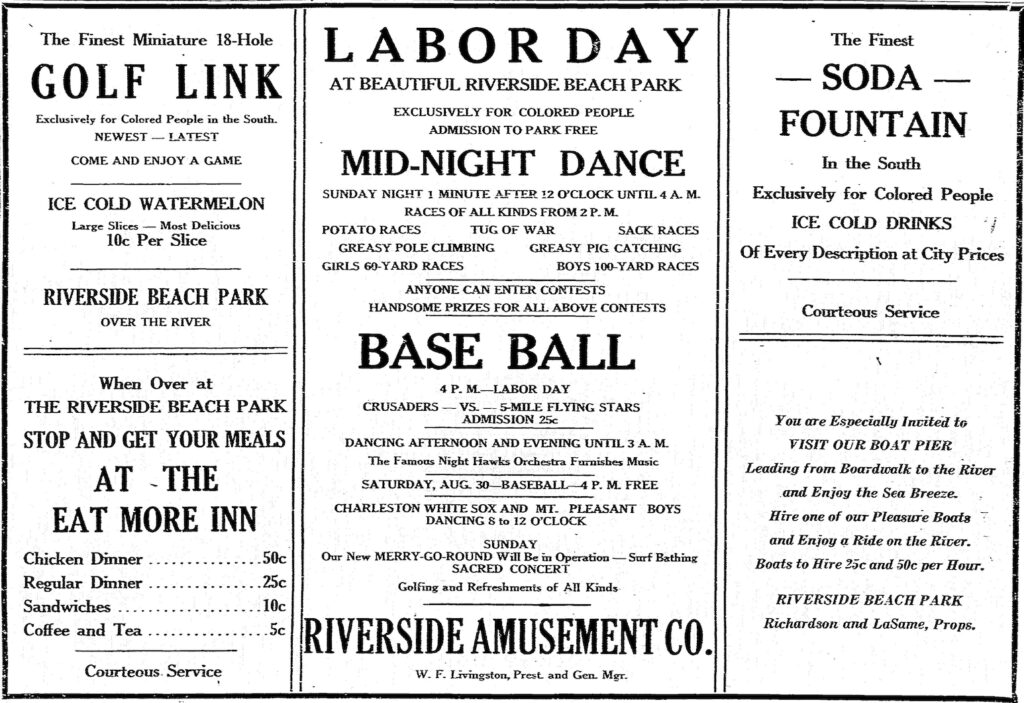

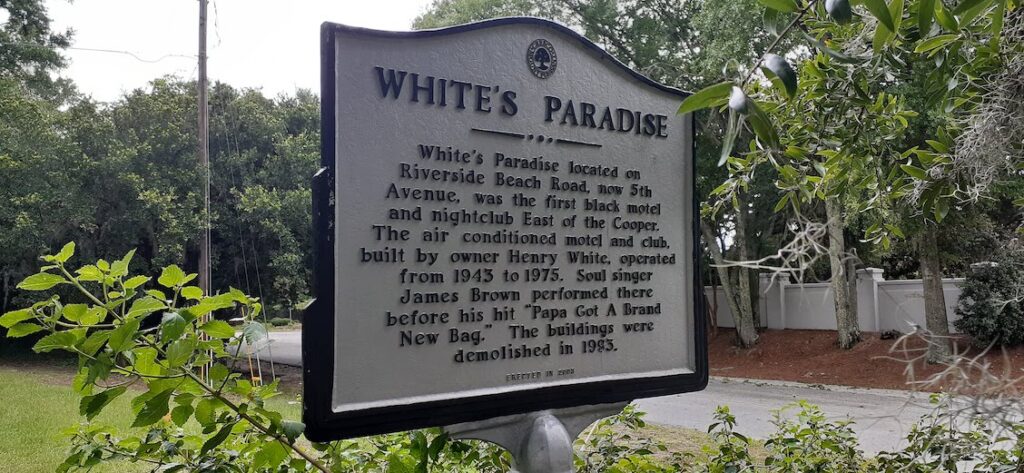

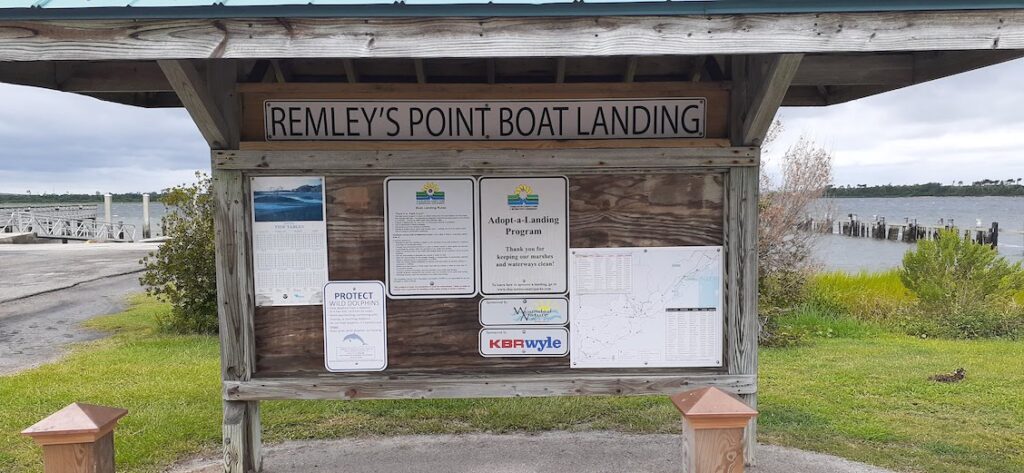

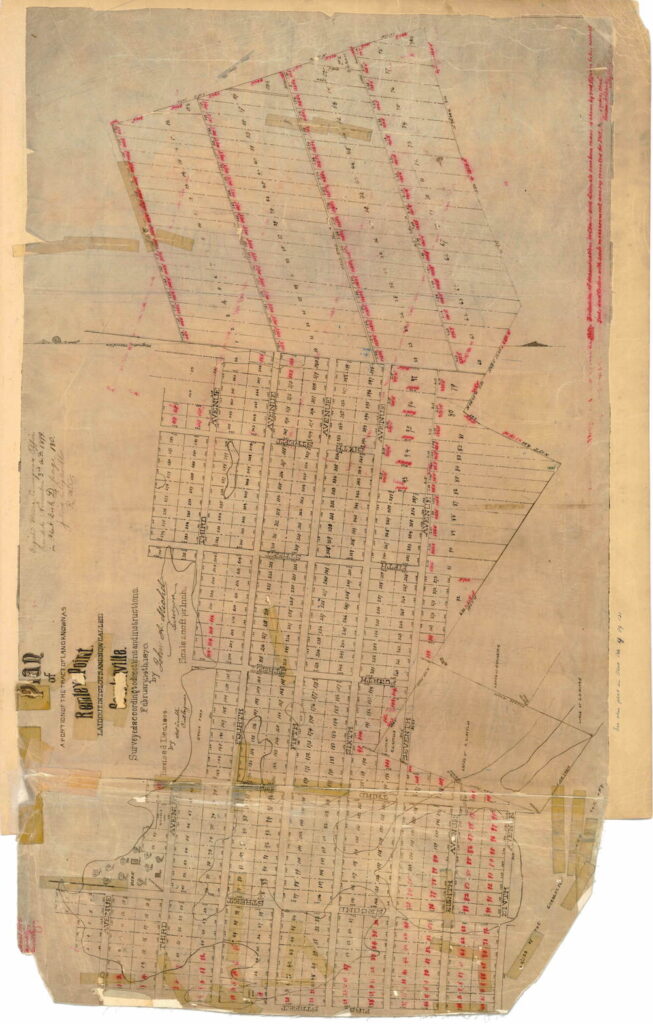

In August 1930, the waterside pavilion of Riverside Beach opened as the first Black beach in the greater Charleston area when African Americans were excluded from many White-only beaches across the Lowcountry. [1] Located on the east bank of the Wando River in Scanlonville, an African American settlement community in Mt. Pleasant, Riverside Beach served as a popular recreational center for Black Charlestonians through the 1970s and offered free admission to a range of amenities including a dance pavilion, baseball games, boardwalks, bathhouses, food and beverage stands, and live music. Riverside Beach notably hosted legendary musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, B.B. King, Fats Domino, Ivory Joe Hunter, and Count Basie, among others. Today, however, the only remnants of this once-thriving venue are a historical marker, erected by the Town of Mt. Pleasant, and a public access boat landing.[2]

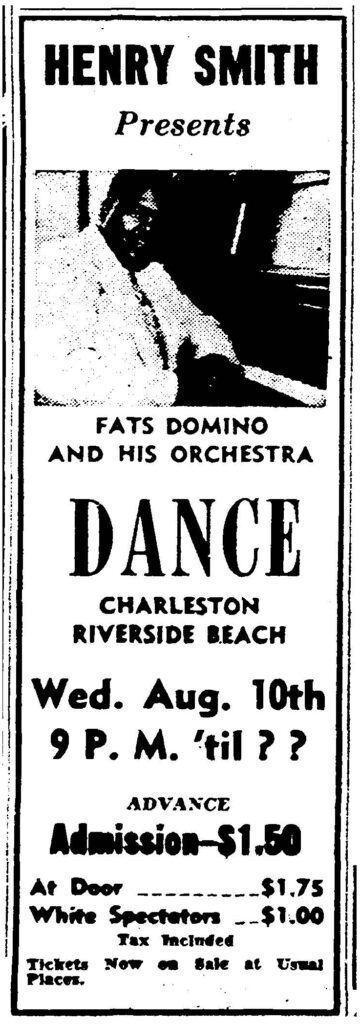

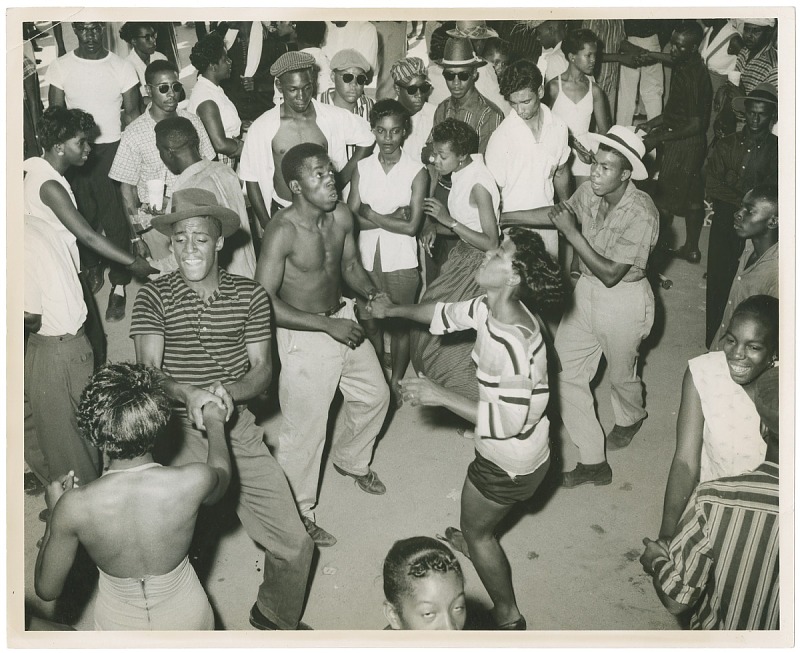

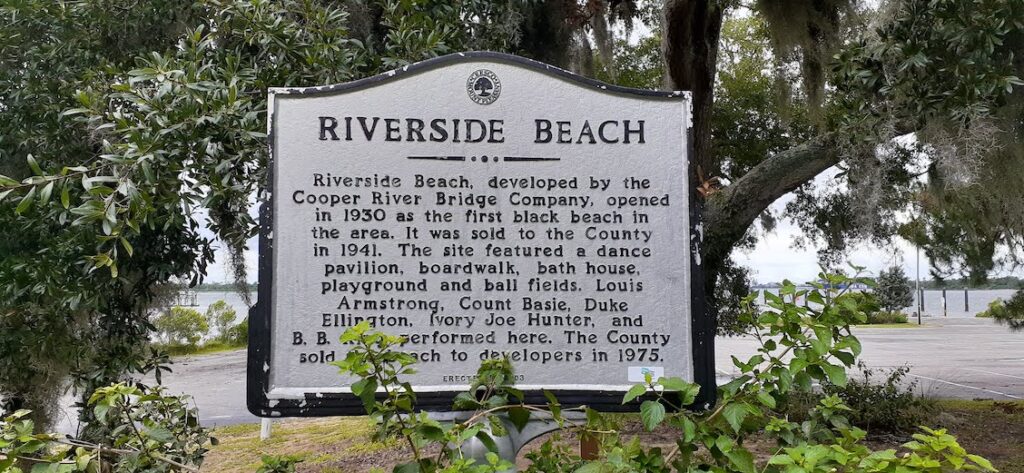

From its opening, Riverside Beach was consistently influenced by African American leadership. The White-owned Cooper River Amusement Company that created Riverside Beach included five Black community members on its Board. When the amusement company went bankrupt in 1936, Charleston County purchased the park in 1941, and continued to lease Riverside Beach primarily to Black managers through the 1970s.[3]

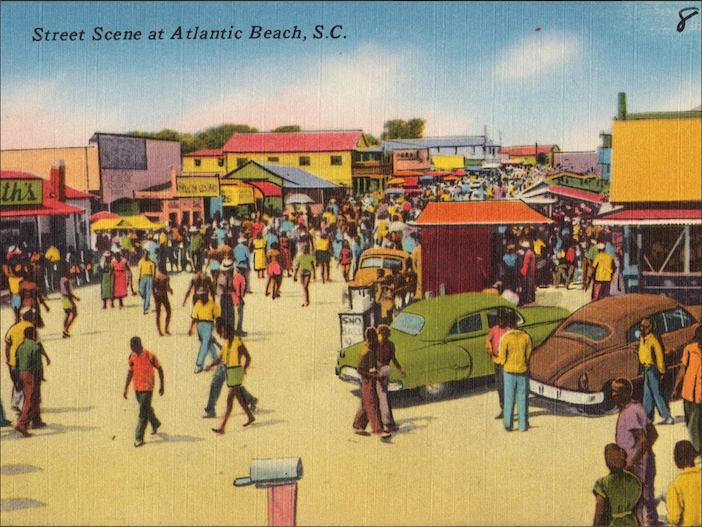

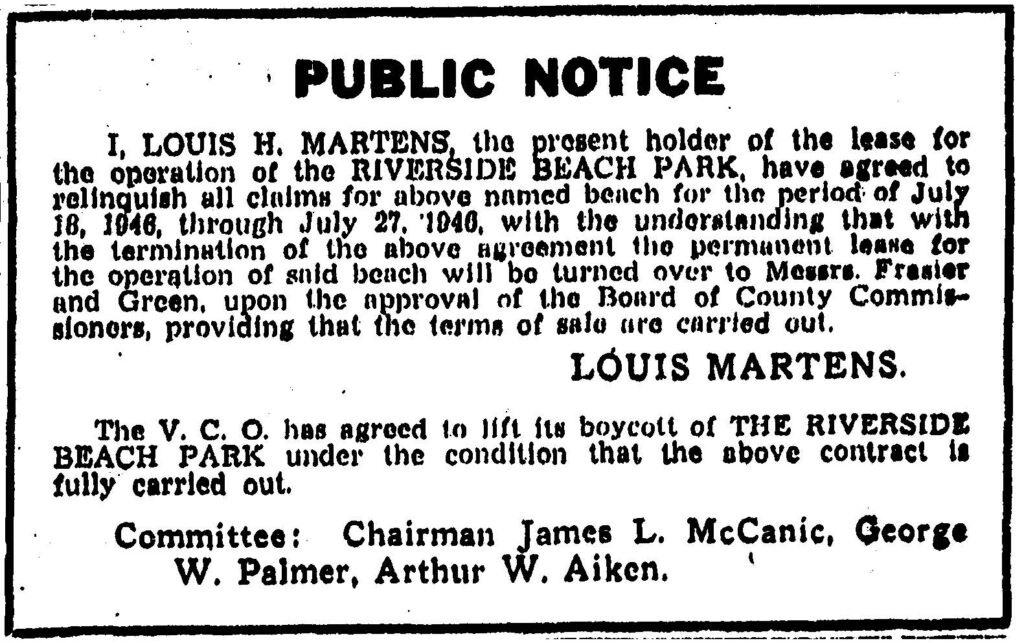

African Americans patrons were proud that the beach was operated by and for Black citizens, which led to boycotts in May 1946 when a White businessman leased the park.[4] The boycott was successful and lessee Louis H. Martens surrendered the lease two months later.[5] With the support of its patrons, Abraham Washington, owner of Reliable Oil Co. and Service Center, and cab driver Edward “Mitch” Mitchell took over the park lease until the 1960s when their partnership ended. Washington continued to operate Riverside Beach until he died in 1975, and the park was sold to developers.[6]

Numerous factors led to the beach’s mid-century decline and eventual closure, including silt deposits on the waterfront from power plant projects on the Cooper River, a reputation for violent crime, and the gradual dilapidation and demolition of structures like the dance pavilion.[7] But perhaps most impactful was the desegregation of oceanfront beaches following the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[8] With new legal access to once-forbidden beaches like Isle of Palms, Folly Beach, or Sullivan’s Island, Riverside Beach drew fewer Black beach-goers over the years. In retrospect, many African American Charlestonians mourned the loss of successful, Black-only sites of leisure, like Riverside Beach. “I was free, and, you know, we could do stuff that we wanted to do,” recalled former WPAL radio station president William Saunders of his youth at Charleston’s Black beaches.[9] Despite the toll desegregation took on Black-owned ventures, business owners, like entrepreneur Albert Brooks, largely asserted they “would not want to go back to the way it was before,” willingly paying the price for justice.[10]

[1] Arthur Lawrence, “Interview of Arthur Lawrence,” interview by Valerie Perry, March 20, 2019, Historic Charleston Foundation Oral History Project, Historic Charleston Foundation, accessed July 1, 2021, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/246474.; Herb Frazier, “Riverside Became a Refuge amid Segregation Lack-Owned Businesses That Thrived around Beaches Gradually Died after Integration,” Post and Courier (Charleston, SC, August 12, 2001).

[2] W. F. Livingston, “Labor Day,” Evening Post (Charleston, SC, August 29, 1930); W. F. Livingston, “Advertisement, Riverside Beach Park,” Evening Post (Charleston, SC, August 8, 1930); Town of Mount Pleasant Historical Commission, “Riverside Beach & White’s Paradise,” Mount Pleasant Historical, accessed June 30, 2021, https://mountpleasanthistorical.org/items/show/54.

[3] “$50,000 Park at Remley’s Point,” Evening Post (Charleston, SC, May 17, 1930).

[4] Albert N. Brooks, “Attention,” Charleston News and Courier (Charleston, SC, May 11, 1946).

[5] Louis Martens, “Public Notice,” Charleston News and Courier (Charleston, SC, July 19, 1946).

[6] Herb Frazier, “Riverside Became a Refuge amid Segregation Lack-Owned Businesses That Thrived around Beaches Gradually Died after Integration,” Post and Courier (Charleston, SC, August 12, 2001).

[7] William G. Wilder, “Interview with William (Cubby) Wilder,” interview by Michael A. Allen, April 14, 2019, Historic Charleston Foundation Oral History Project, Historic Charleston Foundation, accessed July 1, 2021, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/250145.; “St. Stephen’s Fish Lift History,” South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, accessed July 8, 2021, https://www.dnr.sc.gov/timelinestephen/index.html.; Jack Leland, “Fishing Pier Plans,” Evening Post (Charleston, SC, January 31, 1983); “Riverside Beach Pavilion To Go,” Charleston News and Courier (Charleston, SC, April 2, 1958).

[8] Herb Frazier, “Riverside Became a Refuge amid Segregation Lack-Owned Businesses That Thrived around Beaches Gradually Died after Integration.”

[9] William Saunders, “Interview with William Saunders,” interview by Michael A. Allen, June 6, 2019, Historic Charleston Foundation Oral History Project, Historic Charleston Foundation, accessed July 1, 2021, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/250144.

[10] Thomas Mayhem Pinckney Alliance of the Preservation Society of Charleston, “Looking Back / Looking Forward · Morris Street Business District,” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, accessed July 8, 2021, http://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/msbd/looking-back-looking-forward.